![]() Teja: Hey! What did you do to this room? You’ve completely changed the vibe!

Teja: Hey! What did you do to this room? You’ve completely changed the vibe!

![]() Mona: Yep! Since you said we’d be discussing Dravidian personalities today, I thought the setup needed a makeover. I got rid of all the chairs, laid out some carpets and pillows. Now you can sit back and explain everything in style. Oh—and I even arranged a hookah!

Mona: Yep! Since you said we’d be discussing Dravidian personalities today, I thought the setup needed a makeover. I got rid of all the chairs, laid out some carpets and pillows. Now you can sit back and explain everything in style. Oh—and I even arranged a hookah!

![]() Teja: We’re talking about Dravidian Politics, and you’ve given the room an Arabic lounge makeover?

Teja: We’re talking about Dravidian Politics, and you’ve given the room an Arabic lounge makeover?

![]() Mona: I just wanted to make it cozy! And since you’re diving into people’s lives, I figured it might be fun to talk about them like this.

Mona: I just wanted to make it cozy! And since you’re diving into people’s lives, I figured it might be fun to talk about them like this.

![]() Teja: I appreciate the effort, but just so we’re clear—this isn’t going to be a gossip session. It’s about key personalities and their role in shaping Dravidian politics.

Teja: I appreciate the effort, but just so we’re clear—this isn’t going to be a gossip session. It’s about key personalities and their role in shaping Dravidian politics.

![]() Mona: Oh, so you mean the political personalities of Tamil Nadu—like Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Vijay Thalapathy, right? I know stuff about them too!

Mona: Oh, so you mean the political personalities of Tamil Nadu—like Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Vijay Thalapathy, right? I know stuff about them too!

![]() Teja: Hold up. I’m not talking about them—at least not right now. I get that movies and politics go hand in hand in the South, but today, we’re focusing on a different set of people.

Teja: Hold up. I’m not talking about them—at least not right now. I get that movies and politics go hand in hand in the South, but today, we’re focusing on a different set of people.

![]() Mona: Okay, okay… so who are these “others”?

Mona: Okay, okay… so who are these “others”?

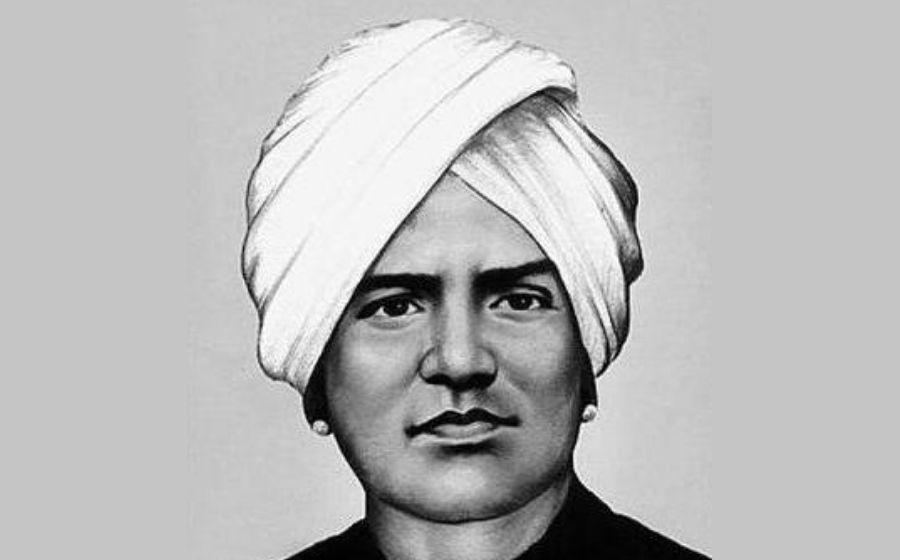

![]() Teja: I’d like to start with Iyothee Thassa Pandithaar. Technically, he’s more of a social reformer than a politician—but an important figure nonetheless. In many ways his ideology was inherited or continued by Ambedkar in the form of Neo Buddhism.

Teja: I’d like to start with Iyothee Thassa Pandithaar. Technically, he’s more of a social reformer than a politician—but an important figure nonetheless. In many ways his ideology was inherited or continued by Ambedkar in the form of Neo Buddhism.

So here’s a bit about him:

Iyothee Thass:

He was born into a Paraiyar(Dalit Community) middle class family(His Grand Father Kandappan worked as a butler of George Harrington) and later adopted his teacher’s name(Iyothee Thass). He is a renowned Siddha practitioner. His real name was Kathavarayan

You could think of him as a figure similar to Jyotirao Phule from Maharashtra.

In fact, he was a pioneer of the Buddhist revival in South India—even before Ambedkar. He converted to Buddhism in 1898 and founded the Sakya Buddha Society.

There are striking similarities between Iyothee Thassa, Ambedkar, and Phule.

He embraced Buddhism as a means of Dalit emancipation and as a stance against Brahminical dominance.

![]() Mona: Buddhism? I like Buddhists—they seem really cute! I’ve seen some in Sikkim and Himachal… all chill and peaceful. Even the Laughing Buddha statues are hilarious!

Mona: Buddhism? I like Buddhists—they seem really cute! I’ve seen some in Sikkim and Himachal… all chill and peaceful. Even the Laughing Buddha statues are hilarious!

And those Buddha-print tees and Nirvana shirts—super cool vibes.

People also tie those colorful flags to their bikes.

So you’re saying Iyothee Thassa started all that? He sounds like a total vibe!

But wait—don’t people also say Buddha is an avatar of Vishnu?

How can that be anti-Brahminical?

![]() Teja: OMG. The things you remember when I say “Buddha” are totally different from what Iyothee Thassa was talking about!

Teja: OMG. The things you remember when I say “Buddha” are totally different from what Iyothee Thassa was talking about!

Let me explain why he chose Buddhism…

Why Buddhism?

- Global Wave of Philosophy:

Buddhism emerged around the 6th century BCE—a time when the world seemed to be in deep thought mode. Great minds like Socrates, Plato, and Confucius were popping up across different civilizations. In India, alongside Jainism, Buddhism took root. Iyothee Thassa believed Buddhism was indigenous and closely aligned with the roots of the Dravidian people.(Around this period, several other philosophical schools also emerged in India, such as Ajivika, Charvaka, and others.) - Reaction to Brahminical Dominance:

Buddhism is often seen as a counter to the ritual-heavy Brahminical practices of the time. Buddha didn’t prescribe complicated yajnas or fire sacrifices. Instead, he promoted Madhyamarga—the Middle Path. No extreme asceticism, no luxurious indulgence—just balance.

(Buddha, aka Siddhartha, came from a Ganasangha—a more egalitarian republic, not a typical hierarchical Janapada. Some believe that the Kshatriyas from these republics weren’t exactly fans of Brahminical supremacy.) - No God, No Problem:

Buddhism is often classified as a Nāstika school. Although Buddha spoke about karma and rebirth, he famously stayed silent on the concept of God.

Originally, Buddha wasn’t worshipped as a deity—people simply followed his teachings. Even today, the Hinayana (Theravāda) sect, especially popular in Sri Lanka, doesn’t treat him as a god. So no temple bells or divine drama here! - No Social Stratification:

Buddhism didn’t come with caste labels. Buddha’s core disciples were from various social backgrounds—take Upali, for instance, who came from a barber community. Everyone had a seat at the table, regardless of their birth. - Beyond Aryavarta:

Dravidian scholars argue that outside the Aryavarta (the northern Vedic heartland), Vedic influence was minimal—especially post 6th century BCE.

Regions like Andhra, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, and parts of Bengal were believed to be strongholds of Buddhism.

It’s also suggested that much of the subcontinent was inhabited by Nagas and various aboriginal communities who didn’t adhere to Vedic traditions.

(But let’s not go there right now—it deserves a full debate of its own!)

![]() Mona: Okay, now I get it! So Iyothee Thass saw Buddhism as an alternative to Hinduism—one without hierarchy or discrimination. In a way, he used Buddhist philosophy to challenge Brahminical dominance. Got it. But tell me this—why not Jainism then?

Mona: Okay, now I get it! So Iyothee Thass saw Buddhism as an alternative to Hinduism—one without hierarchy or discrimination. In a way, he used Buddhist philosophy to challenge Brahminical dominance. Got it. But tell me this—why not Jainism then?

![]() Teja: Well, Jainism is considered quite tough to follow. It demands severe ascetic practices. They believe everything—even a tiny microorganism—has a soul, and they follow extreme non-violence. That makes it hard for people involved in agriculture or everyday labor to live by Jain principles.

Teja: Well, Jainism is considered quite tough to follow. It demands severe ascetic practices. They believe everything—even a tiny microorganism—has a soul, and they follow extreme non-violence. That makes it hard for people involved in agriculture or everyday labor to live by Jain principles.

![]() Mona: Yeah, I seriously don’t know how they survive without eating non-veg! Some Jains don’t even eat veg properly . I once tried going vegan for a few days—total disaster. Couldn’t last!

Mona: Yeah, I seriously don’t know how they survive without eating non-veg! Some Jains don’t even eat veg properly . I once tried going vegan for a few days—total disaster. Couldn’t last!

![]() Teja: Exactly. And unlike Buddhism, Jainism wasn’t promoted by big political figures like Ashoka or Kanishka. Buddha’s Middle Path—Madhyamarga—avoided both extreme rituals and hardcore asceticism, so it was easier for regular folks to join the Sangha and follow.

Teja: Exactly. And unlike Buddhism, Jainism wasn’t promoted by big political figures like Ashoka or Kanishka. Buddha’s Middle Path—Madhyamarga—avoided both extreme rituals and hardcore asceticism, so it was easier for regular folks to join the Sangha and follow.

![]() Mona: But how did they manage to promote their ideology or spread their message back then? There was no social media for quick outreach either.

Mona: But how did they manage to promote their ideology or spread their message back then? There was no social media for quick outreach either.

![]() Teja: They had their own methods. It was mostly through writings and print media. Iyothee Thass, for instance, started a weekly Tamil newspaper called Oru Paisa Tamizhan (One Paise Tamilian) along with Dravidia Pandian to spread his ideas.

Teja: They had their own methods. It was mostly through writings and print media. Iyothee Thass, for instance, started a weekly Tamil newspaper called Oru Paisa Tamizhan (One Paise Tamilian) along with Dravidia Pandian to spread his ideas.

![]() Mona: Hmm… that makes sense. But one last question—if Buddhism had such powerful backing from big names, why are Buddhists in India such a small number today?

Mona: Hmm… that makes sense. But one last question—if Buddhism had such powerful backing from big names, why are Buddhists in India such a small number today?

![]() Teja: There are quite a few reasons behind the decline of Buddhism in India, and I’d like to lay them out for you—some of these are based on M.M. Kane’s views.

Teja: There are quite a few reasons behind the decline of Buddhism in India, and I’d like to lay them out for you—some of these are based on M.M. Kane’s views.

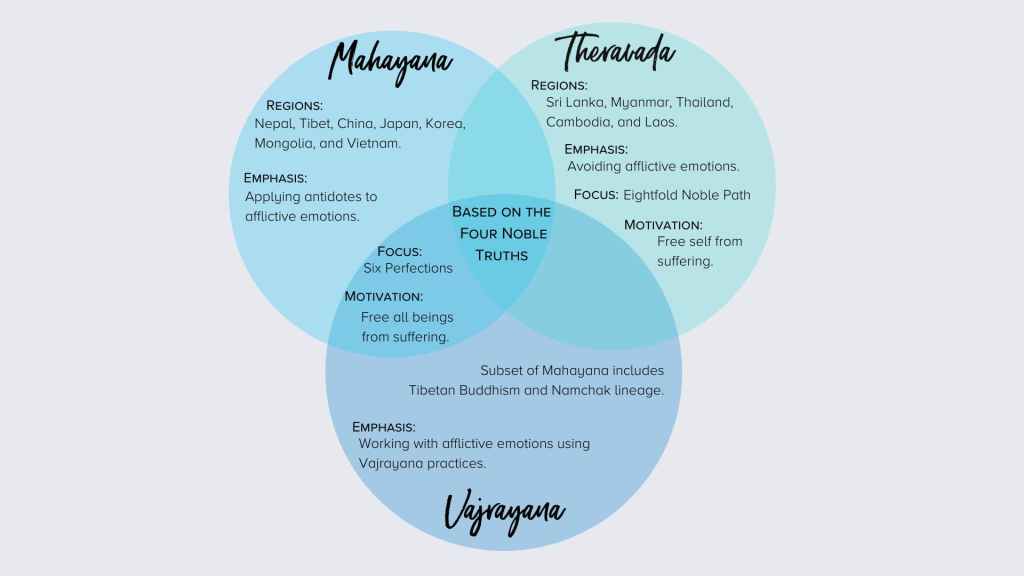

- Internal Division: Buddhism eventually split into multiple sects. After the Fourth Buddhist Council in the 1st century CE, two major branches emerged—Mahayana and Hinayana. Mahayana Buddhism began treating Buddha as a divine figure, almost like a god, which was a big shift from the original teachings.

- Rise of Vajrayana: Then came Vajrayana Buddhism(Tantric Buddhism), which leaned heavily on magic, rituals, and tantrism. Worship of figures like Tara (consorts of Bodhisattvas) became prominent. Historian Rahul Sankrityayan actually blames Vajrayana for the downfall of Buddhism—he believed it diluted the original essence completely.

- Clash and Absorption: Many believe that Buddhism and Hinduism (especially Shaivism) didn’t exactly get along. Over time, Buddha was absorbed into the Hindu fold—as an avatar of Vishnu.

- Loss of Royal Patronage: In its golden age, Buddhism had the support of powerful rulers like Ashoka, Kanishka, and Harshavardhana. But post-Harsha, that support faded. Meanwhile, Hinduism was going through a strong revival, often backed by emerging Rajput dynasties.

- Other Pressures: The advent of Islam, migration of Buddhist scholars, rise of Bhakti and Sufi movements, and reforms within Hinduism itself all added to Buddhism’s decline. It just couldn’t hold the same ground anymore.

![]() Mona: Hey, the discussion seems to have shifted from Iyothee Thassa to Buddhism.

Mona: Hey, the discussion seems to have shifted from Iyothee Thassa to Buddhism.

![]() Teja: Yes, but it’s important to understand the kind of philosophy these reformers aligned with, and the kind of change they were aiming for. Thassa chose Buddhist philosophy as a means to break free from caste-based discrimination. And I already explained why Buddhism was his preferred choice.

Teja: Yes, but it’s important to understand the kind of philosophy these reformers aligned with, and the kind of change they were aiming for. Thassa chose Buddhist philosophy as a means to break free from caste-based discrimination. And I already explained why Buddhism was his preferred choice.

![]() Mona: Actually, all of this is helping me understand his personality much better. So, who’s next on your list?

Mona: Actually, all of this is helping me understand his personality much better. So, who’s next on your list?

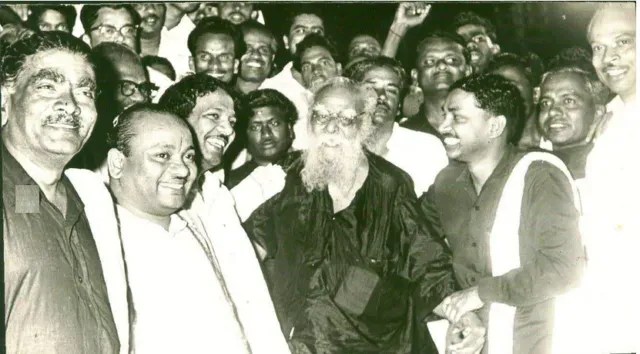

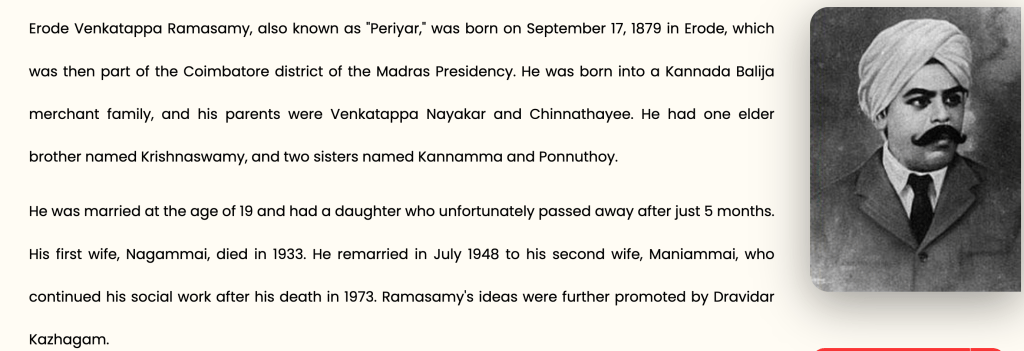

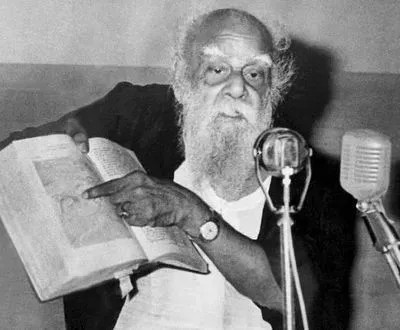

![]() Teja: I’d like to introduce you to Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy( Periyar)—the ultimate Dravidian icon. Fondly called Thanthai Periyar, he’s a very prominent figure.

Teja: I’d like to introduce you to Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy( Periyar)—the ultimate Dravidian icon. Fondly called Thanthai Periyar, he’s a very prominent figure.

![]() Mona: Oh! You’ve mentioned him in passing before. Is he good-looking?

Mona: Oh! You’ve mentioned him in passing before. Is he good-looking?

![]() Teja: Darling, we’re talking about political personalities here, not cover models from fashion magazines!

Teja: Darling, we’re talking about political personalities here, not cover models from fashion magazines!

![]() Mona: I was just curious! You said he’s a Dravidian icon—so I wanted the full picture!

Mona: I was just curious! You said he’s a Dravidian icon—so I wanted the full picture!

![]() Teja: How would I know what he looked like back in the day? Most of the pictures and statues show him with a long beard, grey hair, and a classic philosopher’s aura. But fine, for your satisfaction and in the spirit of being politically correct—I’ll say beauty is subjective, everyone is beautiful in their own way… and yes, Periyar was handsome! Happy?

Teja: How would I know what he looked like back in the day? Most of the pictures and statues show him with a long beard, grey hair, and a classic philosopher’s aura. But fine, for your satisfaction and in the spirit of being politically correct—I’ll say beauty is subjective, everyone is beautiful in their own way… and yes, Periyar was handsome! Happy?

And hey, what if I asked you if Gandhi was handsome?

![]() Mona: Okay, fine! Gandhi is cute. I get it. I’m sorry for asking that—now please continue and tell me about Periyar’s role in Dravidian politics.

Mona: Okay, fine! Gandhi is cute. I get it. I’m sorry for asking that—now please continue and tell me about Periyar’s role in Dravidian politics.

![]() Teja: So, Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy(Periyar) was born into a Balija Naidu family—a Telugu-speaking trading community(few say from Karnataka), generally classified as an upper Shudra caste. He came from a well-to-do merchant background. He dropped out of school early and got involved in the family business.

Teja: So, Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy(Periyar) was born into a Balija Naidu family—a Telugu-speaking trading community(few say from Karnataka), generally classified as an upper Shudra caste. He came from a well-to-do merchant background. He dropped out of school early and got involved in the family business.

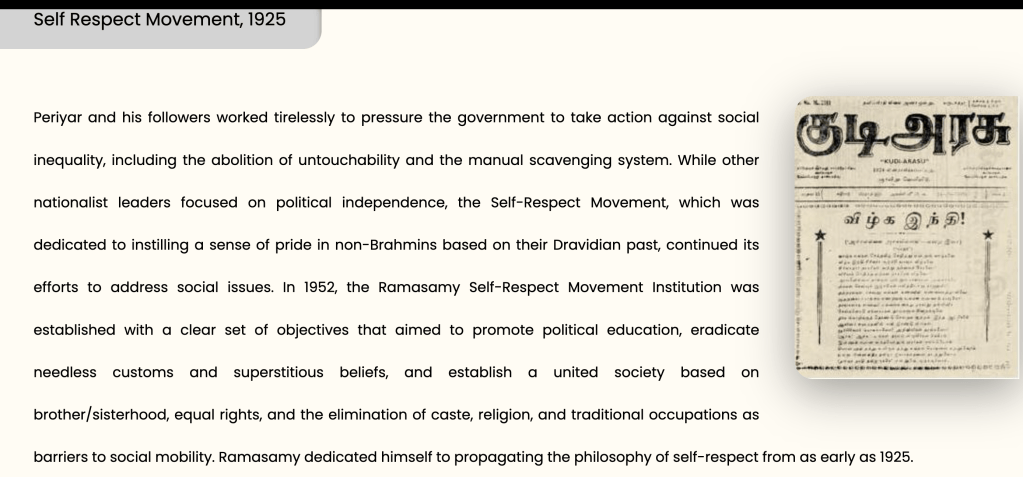

He spread his ideas through newspapers like Kudi Arasu, Viduthalai, and several others.![]() Mona: I’ve noticed—school dropouts always go on to do great things!

Mona: I’ve noticed—school dropouts always go on to do great things!

![]() Teja: In that case, even though you did complete school, you really should’ve attended a few history lectures—it would’ve made my life a lot easier!

Teja: In that case, even though you did complete school, you really should’ve attended a few history lectures—it would’ve made my life a lot easier!

![]() Mona: Ugh! Enough with the mocking. Just help me understand more about Periyar, please.

Mona: Ugh! Enough with the mocking. Just help me understand more about Periyar, please.

![]() Teja: Fine, fine! So, one of the major turning points in Periyar’s(Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy) life was his famous Kasi (Varanasi) experience. He went there on a pilgrimage and visited a South Indian mutt for food. But he was denied food—not because he didn’t have money or wasn’t a devotee, but because he wasn’t a Brahmin.

Teja: Fine, fine! So, one of the major turning points in Periyar’s(Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy) life was his famous Kasi (Varanasi) experience. He went there on a pilgrimage and visited a South Indian mutt for food. But he was denied food—not because he didn’t have money or wasn’t a devotee, but because he wasn’t a Brahmin.

He also saw firsthand how non-Brahmins were barred from entering temple sanctums and how they were systematically discriminated against in religious practices.

To quote him directly:

“At Kashi, I saw the real face of the Brahminical system. I was refused food not because I lacked money or devotion, but because I was not born in the caste they approved. That opened my eyes.”

This incident is believed to have planted the early seeds of the Self-Respect Movement in his mind.

![]() Mona: OMG, that’s so sad! He was discriminated against just for food? That’s seriously unfair. No wonder he started political movements to fight against that kind of injustice.

Mona: OMG, that’s so sad! He was discriminated against just for food? That’s seriously unfair. No wonder he started political movements to fight against that kind of injustice.

![]() Teja: Alright, don’t get too emotional now. Back then, it was quite common for different castes to have their own shelters and food systems in places like Kashi. Most mutts served only people from their own caste. Some even argue that Brahmins weren’t allowed in other caste-based mutts either. But keeping that debate aside, the fact remains—these mutts were closed-off spaces and not very inclusive. Brahmins, however, did seem to enjoy more privilege in the religious sphere.

Teja: Alright, don’t get too emotional now. Back then, it was quite common for different castes to have their own shelters and food systems in places like Kashi. Most mutts served only people from their own caste. Some even argue that Brahmins weren’t allowed in other caste-based mutts either. But keeping that debate aside, the fact remains—these mutts were closed-off spaces and not very inclusive. Brahmins, however, did seem to enjoy more privilege in the religious sphere.

![]() Mona: Hmm, okay. So what exactly is this Self-Respect Movement then?

Mona: Hmm, okay. So what exactly is this Self-Respect Movement then?

![]() Teja: We’ll get to that, but first let me give you a bit more background on Periyar. After the Kashi incident, he launched his movements against caste discrimination and Brahminical dominance.

Teja: We’ll get to that, but first let me give you a bit more background on Periyar. After the Kashi incident, he launched his movements against caste discrimination and Brahminical dominance.

![]() Mona: Oh! So was he, like Iyothee Thass, someone who saw Buddha as the symbol of reform?

Mona: Oh! So was he, like Iyothee Thass, someone who saw Buddha as the symbol of reform?

![]() Teja: That’s exactly what I want to clarify. No, unlike Thass, Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy(Periyar) didn’t choose Buddhism. He took a more radical path—he chose atheism. In the beginning, he focused on pushing for social reforms and was even part of the Indian National Congress before he shifted his focus completely.

Teja: That’s exactly what I want to clarify. No, unlike Thass, Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy(Periyar) didn’t choose Buddhism. He took a more radical path—he chose atheism. In the beginning, he focused on pushing for social reforms and was even part of the Indian National Congress before he shifted his focus completely.

Periyar’s(Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy) Ideology

(Mostly described as being rooted in rationalism, social justice, anti-casteism, and of course, self-respect)(His articles in Kudi Arasu and Vidhtualai are major sources to understand his ideology)

- At the core of Periyar’s belief system was the idea that caste is nothing but a symbol of oppression—a clever tool used by Brahmins to maintain their dominance over the non-Brahmin population in South India. As we touched upon earlier, he viewed the Dvijas (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and to some extent Vaishyas) as belonging to the Aryan race—racially, culturally, and ethnically distinct from the non-Brahmin Dravidians of the South.

- He strongly felt that Dravidian culture had been corrupted by the creeping influence of Vedic traditions. According to him, the original Dravidian society was far more egalitarian and much less hierarchical than the Vedic social order. He accused Brahmins of cunningly absorbing local gods into the Vedic pantheon as a way to culturally hijack the Dravidians. He was a staunch supporter of the Aryan Migration Theory and laid the groundwork for both Dravidian and Tamil nationalism.

- He advocated for a complete cultural detox. Dravidians, he argued, should break free from all Vedic and Sanskrit influence and instead take pride in their own heritage—language, culture, and identity. In his view, self-respect could only grow once the chains of cultural domination were broken.

- Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy(Periyar) also believed that Vedic culture was largely responsible for the subjugation of women. He often compared the status of women in that system to that of Shudras—oppressed and voiceless. According to him, it was Brahminical patriarchy and its traditions that were mainly responsible for gender inequality. . One of his key contributions? Promoting Self-Respect Marriages—free from priests, rituals, and hierarchy.

![]() Mona: He even talked about feminism? Now I’m starting to like him! It’s a woman’s choice, after all. It’s become a habit for male chauvinists to suppress and oppress women. It’s all about women power, women rights…

Mona: He even talked about feminism? Now I’m starting to like him! It’s a woman’s choice, after all. It’s become a habit for male chauvinists to suppress and oppress women. It’s all about women power, women rights…

![]() Teja: Okay, okay, slow down! I get it—you’re a strong feminist, and I truly appreciate that. But let’s not get carried away. Over time, Periyar’s ideology became more radical and even extreme in some aspects. Let me explain:

Teja: Okay, okay, slow down! I get it—you’re a strong feminist, and I truly appreciate that. But let’s not get carried away. Over time, Periyar’s ideology became more radical and even extreme in some aspects. Let me explain:

- He had ideological clashes with C. Rajagopalachari. Rajaji felt that in the name of reform, Tamil Hindu culture was being eroded. Periyar, on the other hand, launched fierce attacks on Hinduism. He criticized Hindu gods in ways that many considered highly offensive. For instance, he called Lord Rama an “Aryan God” and criticized the Ramayana unapologetically.

- Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy(Periyar) went a step further and claimed that all the negative characters in epics like the Mahabharata and Ramayana actually represented Dravidian qualities—while the so-called “heroes” were Aryans. According to him, these epics were tools of Aryan cultural dominance. This gave rise to a wave of reinterpretations in Dravidian literature. Anti-hero narratives became popular. Ravana, for example, was reimagined as a Dravidian icon, while Lord Rama was sharply criticized. (Ironically, Ravana himself is a Brahmin—often referred to as _Ravana Brahma)

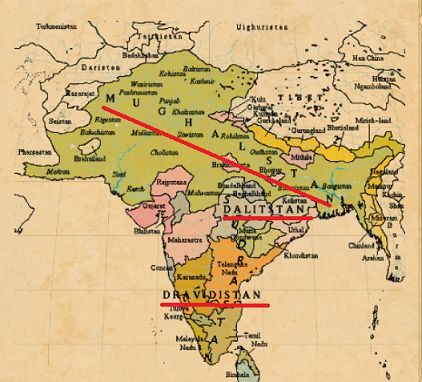

- Ambedkar and Periyar had some common ground, but there were major disagreements too. Many Dalit thinkers felt that the Dravidian movement eventually tilted toward the interests of OBCs and upper Shudra castes, sidelining true Dalit emancipation. During his most extreme phase, Periyar even floated the idea of a separate Dravida Nadu (Dravidian Nation), which Ambedkar completely opposed. For Ambedkar, the unity of India came above everything else

- Even today, you’ll occasionally hear calls for Dravidanadu( Separate Dravidian Nation) in political debates. Periyar’s more extreme statements—like the infamous “If you see a snake and a Brahmin, kill the Brahmin first”—have drawn heavy criticism. While his followers argue he was attacking Brahminism and not Brahmins, such remarks have undeniably created resentment and a perception of targeted hate.

- Communist leaders like E.M.S. Namboodiripad also critiqued him. They believed that Periyar’s movement focused more on cultural identity and caste than on broader class struggle. In other words, it prioritized Dravidian pride over economic reform and workers’ rights.

- Erode Venkatappa Ramasamy(Periyar) also initiated idol-breaking campaigns and led several radical movements that directly targeted religious symbols. These actions were supported by communist groups as well. However, they ended up hurting the religious sentiments of the Hindu population. In some ways, Periyar’s approach seemed to provoke animosity towards a particular community rather than fostering inclusive social reform

![]() Mona: Okay, now I’m starting to grasp the breadth and depth of these personalities. Honestly, I thought you’d just narrate their life stories—you know, like a biopic: childhood, struggle, political rise, and all that.

Mona: Okay, now I’m starting to grasp the breadth and depth of these personalities. Honestly, I thought you’d just narrate their life stories—you know, like a biopic: childhood, struggle, political rise, and all that.

![]() Teja: Ha! I knew it—you’re more into the personal drama than the ideological deep dive. On that note, Periyar’s second marriage at an advanced age was quite controversial. It even caused a rift among his supporters, including Annadurai.

Teja: Ha! I knew it—you’re more into the personal drama than the ideological deep dive. On that note, Periyar’s second marriage at an advanced age was quite controversial. It even caused a rift among his supporters, including Annadurai.

![]() Mona: Actually, I’m finding all this way more interesting than I expected! Understanding their ideologies and the root causes behind their movements really puts things in perspective. Now I see why Periyar’s followers often end up in political controversy—his statements were pretty intense.

Mona: Actually, I’m finding all this way more interesting than I expected! Understanding their ideologies and the root causes behind their movements really puts things in perspective. Now I see why Periyar’s followers often end up in political controversy—his statements were pretty intense.

![]() Teja: Absolutely. Periyar was never the subtle kind—he was radical. He outright blamed Vedic religion (or as he called it, Aryan culture) for most of the societal evils. He didn’t acknowledge any positive contribution from Vedic traditions. He aimed to spread his ideas among OBCs, upper Shudra castes, Dalits, and Dvija women.. He believed upper-caste women were especially oppressed under Brahminical patriarchy. .

Teja: Absolutely. Periyar was never the subtle kind—he was radical. He outright blamed Vedic religion (or as he called it, Aryan culture) for most of the societal evils. He didn’t acknowledge any positive contribution from Vedic traditions. He aimed to spread his ideas among OBCs, upper Shudra castes, Dalits, and Dvija women.. He believed upper-caste women were especially oppressed under Brahminical patriarchy. .

![]() Mona: But isn’t that kind of true? I mean, women were seriously marginalized back then, right?

Mona: But isn’t that kind of true? I mean, women were seriously marginalized back then, right?

![]() Teja: Marginalization of women and feminist thought is a vast topic in itself. What Periyar did was highlight the discriminatory aspects of religious rituals. He famously burned the Manu Smriti, smashed idols, and discouraged the use of Brahmin priests in marriages. However,Hindu Maha Sabha leaders believe that he never really acknowledged the roles women played in Vedic culture—where, historically, many women held prominent and even equal positions. There are plenty of examples of Vedic women who excelled in nearly every sphere, from scholarship to warfare. Think of the Brahmavadinis like Lopamudra Gargi, and the numerous warrior queens in epics—most of them, from Sita to Satyabhama, were not just emotionally strong but also trained in battle. Manu Smriti was Periyar’s go-to text to point out the regressive side of Hindu practices.

Teja: Marginalization of women and feminist thought is a vast topic in itself. What Periyar did was highlight the discriminatory aspects of religious rituals. He famously burned the Manu Smriti, smashed idols, and discouraged the use of Brahmin priests in marriages. However,Hindu Maha Sabha leaders believe that he never really acknowledged the roles women played in Vedic culture—where, historically, many women held prominent and even equal positions. There are plenty of examples of Vedic women who excelled in nearly every sphere, from scholarship to warfare. Think of the Brahmavadinis like Lopamudra Gargi, and the numerous warrior queens in epics—most of them, from Sita to Satyabhama, were not just emotionally strong but also trained in battle. Manu Smriti was Periyar’s go-to text to point out the regressive side of Hindu practices.

![]() Mona: Wait, what exactly is Manu Smriti?

Mona: Wait, what exactly is Manu Smriti?

![]() Teja: Manu is believed to be the first lawgiver in Hindu tradition. Manu Smriti is the legal code attributed to him, and certain sections of it have always been controversial. Vedic scholars argue that, within Vedic tradition, these laws were never meant to be static—they’re supposed to evolve with time and space (kind of like how our Constitution gets amended). There are other legal codes too—like the ones by Parashara and Yagnavalkya—which were followed in different periods. These texts aren’t held as sacred as the Vedas and were meant to adapt. The debate around them? Oh, that never really ends.

Teja: Manu is believed to be the first lawgiver in Hindu tradition. Manu Smriti is the legal code attributed to him, and certain sections of it have always been controversial. Vedic scholars argue that, within Vedic tradition, these laws were never meant to be static—they’re supposed to evolve with time and space (kind of like how our Constitution gets amended). There are other legal codes too—like the ones by Parashara and Yagnavalkya—which were followed in different periods. These texts aren’t held as sacred as the Vedas and were meant to adapt. The debate around them? Oh, that never really ends.

![]() Mona: So, you’re saying he presented only one side of the story? And that, knowingly or unknowingly, his ideology ended up creating divisions—like North vs. South or Dvija vs. Non-Brahmin—rather than uniting people?

Mona: So, you’re saying he presented only one side of the story? And that, knowingly or unknowingly, his ideology ended up creating divisions—like North vs. South or Dvija vs. Non-Brahmin—rather than uniting people?

![]() Teja: In a way, yes. His radical stance might’ve also stemmed from his political experiences. He eventually parted ways with the Congress in the 1920s because he felt the party was dominated by Brahmins and wasn’t serious about social reform. At that time, the Congress chose to focus mainly on political independence, while leaving social reform to be handled by other movements.

Teja: In a way, yes. His radical stance might’ve also stemmed from his political experiences. He eventually parted ways with the Congress in the 1920s because he felt the party was dominated by Brahmins and wasn’t serious about social reform. At that time, the Congress chose to focus mainly on political independence, while leaving social reform to be handled by other movements.

![]() Mona: So he was active on both fronts—political and social reform?

Mona: So he was active on both fronts—political and social reform?

![]() Teja: Exactly. While his ideology has faced criticism for being too radical, his contributions to social reform are widely appreciated—especially his role in the temple entry movement, like the Vaikom Satyagraha. After breaking away from the Congress, he launched the Self-Respect Movement, which eventually evolved into the Dravidar Kazhagam—the ideological parent of today’s DMK and AIADMK.

Teja: Exactly. While his ideology has faced criticism for being too radical, his contributions to social reform are widely appreciated—especially his role in the temple entry movement, like the Vaikom Satyagraha. After breaking away from the Congress, he launched the Self-Respect Movement, which eventually evolved into the Dravidar Kazhagam—the ideological parent of today’s DMK and AIADMK.

![]() Mona: Ah, now it makes sense why he’s called the Father of the Dravidian Movement!

Mona: Ah, now it makes sense why he’s called the Father of the Dravidian Movement!

![]() Teja: Yup! And you’ll be hearing his name a lot more as we dive deeper into other key Dravidian leaders, parties, and their influence.

Teja: Yup! And you’ll be hearing his name a lot more as we dive deeper into other key Dravidian leaders, parties, and their influence.

Discover more from The Critilizers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.