Shaila Bano: As-salamu alaykum, Sekhar! Did you book the tickets to Kashmir? We really have to go, and I’ll introduce you to my family.

Shaila Bano: As-salamu alaykum, Sekhar! Did you book the tickets to Kashmir? We really have to go, and I’ll introduce you to my family.

Sekhar: How many times are you going to introduce me? I already met your parents when they came to Hyderabad, remember?

Sekhar: How many times are you going to introduce me? I already met your parents when they came to Hyderabad, remember?

Shaila Bano: No, this time I’ll introduce you to my mama, chacha, and also take you to my nanihal and so on.

Shaila Bano: No, this time I’ll introduce you to my mama, chacha, and also take you to my nanihal and so on.

Sekhar: Hold on! Are you planning something? Don’t tell me all these people will gang up on me once they find out about us. Look, all that teasing I did was just for fun. If you’re plotting something, you’d better confess right here and now!

Sekhar: Hold on! Are you planning something? Don’t tell me all these people will gang up on me once they find out about us. Look, all that teasing I did was just for fun. If you’re plotting something, you’d better confess right here and now!

Shaila Bano: Oh, shut up! I just want to show you Kashmir and introduce you to my folks. You don’t know how welcoming we are—we’re famous for our mehman nawazi!

Shaila Bano: Oh, shut up! I just want to show you Kashmir and introduce you to my folks. You don’t know how welcoming we are—we’re famous for our mehman nawazi!

Sekhar: Okay, okay, fine. But tell me more about Kashmir. I’ve never been there. All I’ve heard is that it’s a Muslim-majority region with border issues and all those controversies you see in the news.

Sekhar: Okay, okay, fine. But tell me more about Kashmir. I’ve never been there. All I’ve heard is that it’s a Muslim-majority region with border issues and all those controversies you see in the news.

Shaila Bano: Kashmir is called Jannat—heaven on earth—and it truly is such a beautiful place, there’s no doubt about it. I know you’ve probably heard all sorts of things and formed your own image. But keeping all the controversies aside, I really love my homeland.

Shaila Bano: Kashmir is called Jannat—heaven on earth—and it truly is such a beautiful place, there’s no doubt about it. I know you’ve probably heard all sorts of things and formed your own image. But keeping all the controversies aside, I really love my homeland.

Sekhar: Okay, but all we ever hear are things like communal tensions, border issues, and separatist problems, right?

Sekhar: Okay, but all we ever hear are things like communal tensions, border issues, and separatist problems, right?

Shaila Bano: That may be what it’s known for now, but Kashmir has its own rich history too. And not just as a student of History and Political Science, but as a Kashmiri myself, I feel I must teach you about it. Even for my sake, you need to know Kashmir.

Shaila Bano: That may be what it’s known for now, but Kashmir has its own rich history too. And not just as a student of History and Political Science, but as a Kashmiri myself, I feel I must teach you about it. Even for my sake, you need to know Kashmir.

Sekhar: Hmm, if you know things in such detail, then go ahead—explain.

Sekhar: Hmm, if you know things in such detail, then go ahead—explain.

Shaila Bano: Where should I start… Alright, I’ll begin with the society of Kashmir.

Shaila Bano: Where should I start… Alright, I’ll begin with the society of Kashmir.

Sekhar: What’s there to know about it? The majority is Muslim, and the Pandits were made to vacate. Isn’t it basically just one community now? This is exactly why I worry—I don’t know how they’ll react to me! (mockingly)

Sekhar: What’s there to know about it? The majority is Muslim, and the Pandits were made to vacate. Isn’t it basically just one community now? This is exactly why I worry—I don’t know how they’ll react to me! (mockingly)

Shaila Bano: Sekhar, please stop talking and just listen. For now, keep our issue aside. You really know nothing about Kashmir. I’m not denying the events that happened—I’ll talk about them too, with facts from both sides, so you can decide for yourself. But don’t rush me. For now, I’ll start with the ancient society of Kashmir.

Shaila Bano: Sekhar, please stop talking and just listen. For now, keep our issue aside. You really know nothing about Kashmir. I’m not denying the events that happened—I’ll talk about them too, with facts from both sides, so you can decide for yourself. But don’t rush me. For now, I’ll start with the ancient society of Kashmir.

Sekhar: Don’t get into angry mode, Shaila. I’m only pulling your leg. Explain it to me gently.

Sekhar: Don’t get into angry mode, Shaila. I’m only pulling your leg. Explain it to me gently.

Shaila Bano: Ancient Kashmiri society and culture actually pre-date the birth of Islam. Even Indus Valley sites have been found in Kashmir—Manda, for example, is a famous IVC site in Jammu (yes, I know it’s not exactly in Kashmir). You already know how the Indus Valley Civilization was—its urban planning and its forms of worship. After the Indus Valley period came the Iron Age. And during the Iron Age, there’s something Kashmir had in common with Andhra, I mean South India.

Shaila Bano: Ancient Kashmiri society and culture actually pre-date the birth of Islam. Even Indus Valley sites have been found in Kashmir—Manda, for example, is a famous IVC site in Jammu (yes, I know it’s not exactly in Kashmir). You already know how the Indus Valley Civilization was—its urban planning and its forms of worship. After the Indus Valley period came the Iron Age. And during the Iron Age, there’s something Kashmir had in common with Andhra, I mean South India.

Sekhar: Ah, so at least we have one thing in common!

Sekhar: Ah, so at least we have one thing in common!

Shaila Bano: Burzahom is a site in Srinagar that dates back to the Iron Age. Now, during this period, in most of northern India (the former Indus Valley regions extending into the Indo-Gangetic plains), Vedic culture was prevalent. But in the Kashmir Valley and in Southern India, it was the Megalithic culture that dominated. By Megalithic, I mean monumental stone structures used in rituals and burials, though with slight variations.

Shaila Bano: Burzahom is a site in Srinagar that dates back to the Iron Age. Now, during this period, in most of northern India (the former Indus Valley regions extending into the Indo-Gangetic plains), Vedic culture was prevalent. But in the Kashmir Valley and in Southern India, it was the Megalithic culture that dominated. By Megalithic, I mean monumental stone structures used in rituals and burials, though with slight variations.

Sekhar: So you’re saying there was no distinctive Vedic religion in these two regions during that period?

Sekhar: So you’re saying there was no distinctive Vedic religion in these two regions during that period?

Shaila Bano: Exactly. Historians argue that there wasn’t a clear Vedic phase in South India or in the Kashmir Valley. Until the rise of the Mahajanapadas (the formation of kingdoms like Magadha, Avanti, and so on), the culture in these two regions—Kashmir and the South—is referred to as Megalithic culture.

Shaila Bano: Exactly. Historians argue that there wasn’t a clear Vedic phase in South India or in the Kashmir Valley. Until the rise of the Mahajanapadas (the formation of kingdoms like Magadha, Avanti, and so on), the culture in these two regions—Kashmir and the South—is referred to as Megalithic culture.

Sekhar: Okay… I’ve got a vague idea now, but honestly, a lot of things are still unclear to me.

Sekhar: Okay… I’ve got a vague idea now, but honestly, a lot of things are still unclear to me.

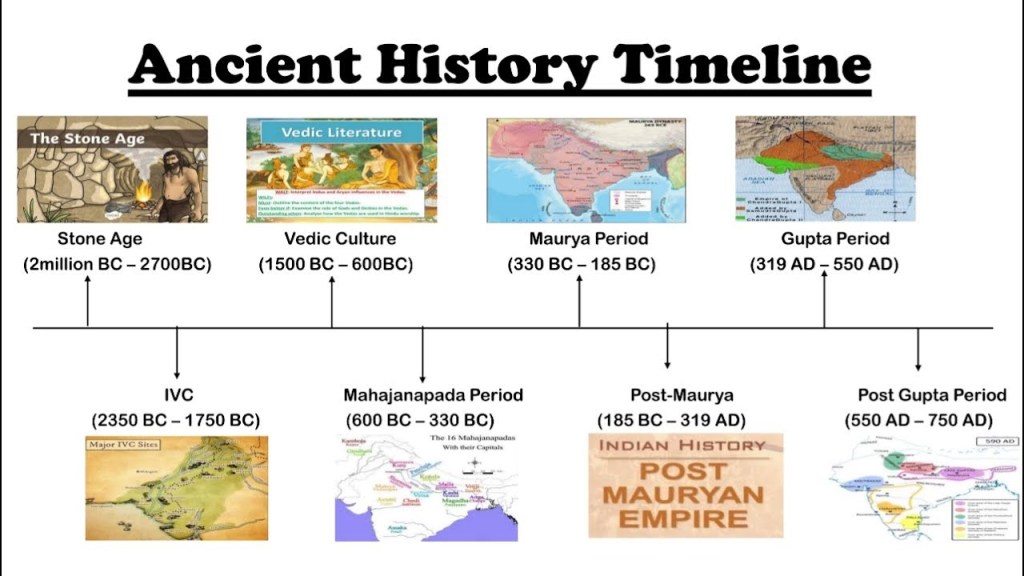

Shaila Bano: Alright then, let me not confuse you further. I’ll simplify it for you.So, the overall ancient history timeline (the broadly accepted one) goes like this: first the Indus Valley Civilization, followed by the Vedic or Aryan Civilization, then the Mahajanapada period with its 16 republics and kingdoms. After that comes the Mauryan period, followed by the post-Mauryan kingdoms like the Sungas, then the early foreign invasions. Next is the Gupta period and later Harshavardhana. After the Gupta age, it’s mostly the disintegration of empire and the rise of feudal powers and other medieval kingdoms.

Shaila Bano: Alright then, let me not confuse you further. I’ll simplify it for you.So, the overall ancient history timeline (the broadly accepted one) goes like this: first the Indus Valley Civilization, followed by the Vedic or Aryan Civilization, then the Mahajanapada period with its 16 republics and kingdoms. After that comes the Mauryan period, followed by the post-Mauryan kingdoms like the Sungas, then the early foreign invasions. Next is the Gupta period and later Harshavardhana. After the Gupta age, it’s mostly the disintegration of empire and the rise of feudal powers and other medieval kingdoms.

Is the broad timeline clear?

Sekhar: Okay, now I get it. This is basically the broad framework of Indian history. And within that, there are regional variations—like the South had its own Sangam period when the rest of India was under the Mauryan era. Similarly, the Kashmir Valley had its own unique trajectory.

Sekhar: Okay, now I get it. This is basically the broad framework of Indian history. And within that, there are regional variations—like the South had its own Sangam period when the rest of India was under the Mauryan era. Similarly, the Kashmir Valley had its own unique trajectory.

Shaila Bano: Yes, and now let me take you through Kashmiri society and culture in the periods after the Indus Valley.

Shaila Bano: Yes, and now let me take you through Kashmiri society and culture in the periods after the Indus Valley.

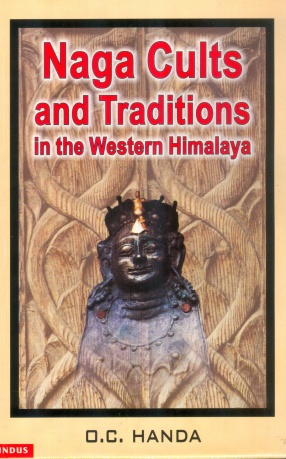

The Nagas:

During the Iron Age, Kashmiri religion was heavily influenced by Naga culture—serpent worship. It’s believed that several hill tribes lived in the valley, and their culture was dominant. Tribes like the Nishadas, Kiratas, Gandharas, and others. The exact origin of the snake cult isn’t clear. There’s even a famous story about how Majjhantika, a Buddhist monk sent by Ashoka’s advisor, convinced the Naga King Aravala to accept Buddhism. (This story comes from the Mahavamsa, a Sri Lankan Buddhist text). And look at the place names in Kashmir: Anantnag, Verinag, Kokernag, Sernag—“nag” also refers to water springs.

Sekhar: Wait, but isn’t Naga worship also part of Hindu or Vedic culture?

Sekhar: Wait, but isn’t Naga worship also part of Hindu or Vedic culture?

Shaila Bano: That’s where the debates start. Leftist scholars usually argue that Naga worship was an indigenous tribal or aboriginal practice, since Vedic culture focused more on deities like Agni and Varuna. There’s a huge discussion around this. For example, Dravidian thinkers in the South differentiate Murugan (Subramanya) worship as indigenous to their land. They claim several local gods are unique to their culture and don’t fit neatly into the broader Hindu or Vedic fold, which they often call “Brahminical culture,” usually associated with Brahmins and Rajputs. On the other hand, thinkers like Ghurye argue that these practices ultimately fall within the broader Hindu tradition.

Shaila Bano: That’s where the debates start. Leftist scholars usually argue that Naga worship was an indigenous tribal or aboriginal practice, since Vedic culture focused more on deities like Agni and Varuna. There’s a huge discussion around this. For example, Dravidian thinkers in the South differentiate Murugan (Subramanya) worship as indigenous to their land. They claim several local gods are unique to their culture and don’t fit neatly into the broader Hindu or Vedic fold, which they often call “Brahminical culture,” usually associated with Brahmins and Rajputs. On the other hand, thinkers like Ghurye argue that these practices ultimately fall within the broader Hindu tradition.

Sekhar: One more common thing between Kashmir and the South. I came across something similar about the origin of the Satavahanas—that they were born from the union of a Brahmin king and a Naga woman, or maybe the other way around. If I’m not mistaken, the fiction writer Amish Tripathi also uses a lot of Naga references in his books—The Immortals of Meluha (the Shiva Trilogy) and even in his latest series.

Sekhar: One more common thing between Kashmir and the South. I came across something similar about the origin of the Satavahanas—that they were born from the union of a Brahmin king and a Naga woman, or maybe the other way around. If I’m not mistaken, the fiction writer Amish Tripathi also uses a lot of Naga references in his books—The Immortals of Meluha (the Shiva Trilogy) and even in his latest series.

Shaila Bano: Waah, Sekhar! I did not expect this from you. Quoting Amish is already a big surprise, but talking about the Satavahanas—that’s way out of the box! Yes, there are indeed different theories about their origin involving Nagas, as you mentioned. (Jinaprabhasuri and Prajusliski write about this too.) Jain and Buddhist scriptures often say the same. But honestly, the biggest surprise is that you know this—you don’t even read the newspaper! How did you come across all this?

Shaila Bano: Waah, Sekhar! I did not expect this from you. Quoting Amish is already a big surprise, but talking about the Satavahanas—that’s way out of the box! Yes, there are indeed different theories about their origin involving Nagas, as you mentioned. (Jinaprabhasuri and Prajusliski write about this too.) Jain and Buddhist scriptures often say the same. But honestly, the biggest surprise is that you know this—you don’t even read the newspaper! How did you come across all this?

Sekhar: All your books are lying around. The Satavahana book caught my eye since they’re from my region, but I couldn’t get past the origin stories—it felt boring. Then I jumped straight to the fiction. In the process of trying to impress you, I ended up pulling this dangerous stunt. Now go on, continue.

Sekhar: All your books are lying around. The Satavahana book caught my eye since they’re from my region, but I couldn’t get past the origin stories—it felt boring. Then I jumped straight to the fiction. In the process of trying to impress you, I ended up pulling this dangerous stunt. Now go on, continue.

Shaila Bano: Wolla habibi, I’m impressed! Even Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang, Tsiuki) mentions the story of Majjhantika and how this Buddhist scholar saved the valley from the Nagas. The Nilamatapurana also describes how the valley was created out of a lake, with the responsibility of protecting it given to the Nagas. Their role in the Iramanjari Pooja during the month of Chaitra is another example. “Nag” also means springs, which is why many temples were built around them. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, the major source for Kashmiri history, describes Kashmir as a land protected by Nila, the lord of the Nagas. Even though Buddhism later undermined Naga beliefs, Naga Mahapadma remained the tutelary deity of Wular Lake.

Shaila Bano: Wolla habibi, I’m impressed! Even Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang, Tsiuki) mentions the story of Majjhantika and how this Buddhist scholar saved the valley from the Nagas. The Nilamatapurana also describes how the valley was created out of a lake, with the responsibility of protecting it given to the Nagas. Their role in the Iramanjari Pooja during the month of Chaitra is another example. “Nag” also means springs, which is why many temples were built around them. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, the major source for Kashmiri history, describes Kashmir as a land protected by Nila, the lord of the Nagas. Even though Buddhism later undermined Naga beliefs, Naga Mahapadma remained the tutelary deity of Wular Lake.

Sekhar: So, the ancient culture of Kashmir was dominated by the Naga cult, and then Buddhism arrived in the valley during Mauryan times—around the 3rd century BC, right?

Sekhar: So, the ancient culture of Kashmir was dominated by the Naga cult, and then Buddhism arrived in the valley during Mauryan times—around the 3rd century BC, right?

Buddhism:

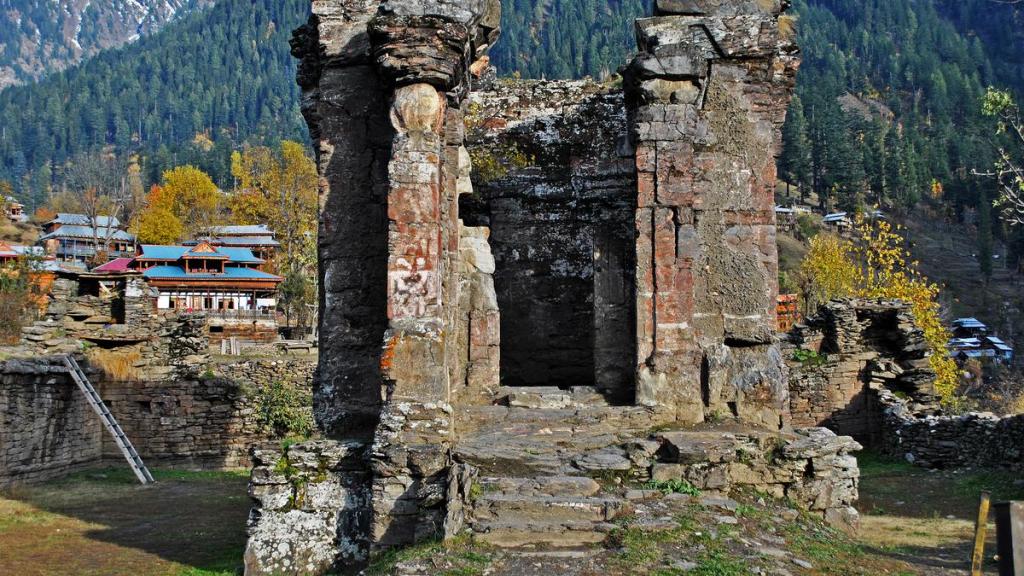

Shaila Bano: Yes. According to the Mahavamsa, the story of Majjhantika and the Naga King Aravala marks the beginning of Buddhism in Kashmir. After Ashoka, there isn’t much clear information about Buddhism, but by the 1st century BC we hear the famous story of the Greek king Meander being converted to Buddhism by Nagasena. Then, during the reign of Kanishka (1st century AD), the fourth Buddhist council was held in Kashmir, and Buddhism split into Mahayana and Hinayana sects. The great Buddhist scholar Nagarjuna also lived in Kashmir during the Kushan period—though it’s believed he was born in southern India. Later, kings like Pravarasena in the 6th century AD still patronized Buddhism, but after the Kushans, it began to slowly decline in the valley.

Shaila Bano: Yes. According to the Mahavamsa, the story of Majjhantika and the Naga King Aravala marks the beginning of Buddhism in Kashmir. After Ashoka, there isn’t much clear information about Buddhism, but by the 1st century BC we hear the famous story of the Greek king Meander being converted to Buddhism by Nagasena. Then, during the reign of Kanishka (1st century AD), the fourth Buddhist council was held in Kashmir, and Buddhism split into Mahayana and Hinayana sects. The great Buddhist scholar Nagarjuna also lived in Kashmir during the Kushan period—though it’s believed he was born in southern India. Later, kings like Pravarasena in the 6th century AD still patronized Buddhism, but after the Kushans, it began to slowly decline in the valley.

Sekhar: Post-Mauryas, there were foreign kingdoms like the Indo-Greeks (after Alexander’s invasion), the Parthians, the Scythians (Sakas), and the Kushans, in that order, right? And King Meander and Kanishka belong to those periods?

Sekhar: Post-Mauryas, there were foreign kingdoms like the Indo-Greeks (after Alexander’s invasion), the Parthians, the Scythians (Sakas), and the Kushans, in that order, right? And King Meander and Kanishka belong to those periods?

Shaila Bano: Exactly, you can connect it like that. Hiuen Tsang and Kalhana both mention a stupa in the Gilgit region, and manuscripts even mention a Shahi king named Srideva Sahi Surendra Vikramaditya Nanda. A number of Buddhist sculptures have also been found at Pandrethan. Another Chinese traveler, Ou-kong, visited Kashmir in the 7th–8th century AD. He studied the Vinayas of the Mulasarvastivadins, and his accounts give us more details about Buddhism in the valley.

Shaila Bano: Exactly, you can connect it like that. Hiuen Tsang and Kalhana both mention a stupa in the Gilgit region, and manuscripts even mention a Shahi king named Srideva Sahi Surendra Vikramaditya Nanda. A number of Buddhist sculptures have also been found at Pandrethan. Another Chinese traveler, Ou-kong, visited Kashmir in the 7th–8th century AD. He studied the Vinayas of the Mulasarvastivadins, and his accounts give us more details about Buddhism in the valley.

Slowly, though, with the rise of Shaiva and Vaishnava faiths, Buddhism lost ground in Kashmir. The decline followed a pattern similar to the rest of India. Historians argue that Shaivites were often hostile toward Buddhism, while Vaishnavites absorbed Buddha as one of Vishnu’s avatars. Later, with the birth of Islam and its arrival in India, Buddhism could not revive.

Sekhar: So what about Hinduism in the valley then? Should the Naga culture be considered part of Hindu origins there?

Sekhar: So what about Hinduism in the valley then? Should the Naga culture be considered part of Hindu origins there?

Shaila Bano: No, let’s keep the Naga debate aside for now and move into Hinduism in the valley.

Shaila Bano: No, let’s keep the Naga debate aside for now and move into Hinduism in the valley.

Hinduism:

There’s a mythological story about the origin of Kashmir—that it emerged from a vast lake called Satisaras (as mentioned in Hindu texts). The draining of this lake is attributed to Sage Kashyapa. Even Abul Fazl (one of Akbar’s nine jewels, who wrote the Ain-i-Akbari) mentions the origin of Kashmir as being linked to the lake of Uma (the wife of Shiva).

Some accounts also say that Nila assigned the responsibility of the land to Kashyapa. In the Nilamat Purana, there’s a story that the land was allowed for human beings to dwell in only during six months of the year. In winter, they had to move out of the valley, which was then inhabited by pisachas (spirits). But with the prayers of a Brahmin named Chandradeva, humans eventually began residing there year-round. (Maybe this was a mythological way of explaining transhumance. Even today, during Chillai Kalan—the harsh winter—many Kashmiris move outside the valley to places like Delhi and elsewhere.)

Sekhar: But all these are mythological accounts for Hindu origins in the valley, right? What about the historical point of view?

Sekhar: But all these are mythological accounts for Hindu origins in the valley, right? What about the historical point of view?

Shaila Bano: That can be seen through the prism of Shaivism. Kashmiri Shaivism is very famous and well known.

Shaila Bano: That can be seen through the prism of Shaivism. Kashmiri Shaivism is very famous and well known.

Shaivism:

Shaila Bano: There’s evidence of proto-Shiva worship in the Indus Valley Civilization, like the famous Pashupathi seal. Since an Indus Valley site has been found in J&K, some people take this as the root of Hinduism. As I mentioned earlier, certain scholars differentiate the gods of the Indus Valley from those of the Vedic tradition, arguing that Indus Valley deities were more like local or regional gods, mostly worshipped by non-Brahmin groups. In fact, a few Shaivite scholars even separate Shaivism from Vedic Hinduism, claiming that Shaivism predates Vedic culture altogether.

Sekhar: Ah, now it’s slowly making sense. So it’s like everyone is trying to claim the older ancestry and origins, based on texts and other sources.

Sekhar: Ah, now it’s slowly making sense. So it’s like everyone is trying to claim the older ancestry and origins, based on texts and other sources.

Shaila Bano: Exactly. And Shaivism in Kashmir also received royal patronage—from the Karkota, Utpala, and Lohara rulers. Early Shaivism here was of the Pashupatha sect, which was based mostly on dualism. From the 8th century AD, under the influence of Shankaracharya, Shaivism in Kashmir took the shape of Advaita Siddhanta (idealistic monism). Interestingly, Advaita Siddhanta is very similar to the Sufi Islamic concept of Wahdat ul-Wujud (unity of existence). Vasugupta was also a proponent of a similar doctrine, known as Trika Shastra.

Shaila Bano: Exactly. And Shaivism in Kashmir also received royal patronage—from the Karkota, Utpala, and Lohara rulers. Early Shaivism here was of the Pashupatha sect, which was based mostly on dualism. From the 8th century AD, under the influence of Shankaracharya, Shaivism in Kashmir took the shape of Advaita Siddhanta (idealistic monism). Interestingly, Advaita Siddhanta is very similar to the Sufi Islamic concept of Wahdat ul-Wujud (unity of existence). Vasugupta was also a proponent of a similar doctrine, known as Trika Shastra.

During the Karkota dynasty, both Shaivism and Vaishnavism were popular. Among the incarnations of Vishnu, Varaha and Narasimha were especially worshipped in Kashmir. Along with Shiva and Vishnu, other gods like Surya, Kartikeya, Ganesha, Lakshmi, and Durga were also venerated. Some scholars even trace the worship of Surya here to Iranian, Kushan, and Saka influences—the famous Sun Temple of Martand is the best example (but let’s not go into all those details now!).

And of course, Goddess Sharada was one of the most celebrated deities of Kashmir—the famous Sharada Peeth.

Sekhar: Goddess Sharada? So that means Shaktism was also present in Kashmir!

Sekhar: Goddess Sharada? So that means Shaktism was also present in Kashmir!

Shaila Bano: Yes, and the mention of the Sapta Matrikas—Brahmani, Indrani, Vaishnavi, Varahi, and Chamundi—has been recorded from Pandrethan and is also mentioned in the Rajatarangini.

Shaila Bano: Yes, and the mention of the Sapta Matrikas—Brahmani, Indrani, Vaishnavi, Varahi, and Chamundi—has been recorded from Pandrethan and is also mentioned in the Rajatarangini.

Sekhar: Wow, so almost all the sects of Hinduism were present in the valley!

Sekhar: Wow, so almost all the sects of Hinduism were present in the valley!

Shaila Bano: That’s right. There’s even a Christian belief that King Solomon visited Kashmir. And all of this predates the birth of Islam.

Shaila Bano: That’s right. There’s even a Christian belief that King Solomon visited Kashmir. And all of this predates the birth of Islam.

Sekhar: Okay, the religious angle is clear now. But what about society in the valley? You’ve told me about Naga culture, Buddhism, and Hinduism. Was society divided according to the four-fold Varna model—Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra?

Sekhar: Okay, the religious angle is clear now. But what about society in the valley? You’ve told me about Naga culture, Buddhism, and Hinduism. Was society divided according to the four-fold Varna model—Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra?

Shaila Bano: Brahmins were definitely present—it’s called the “land of rishis,” after all. But, similar to southern India, society was basically Brahmins and non-Brahmins. The valley was dominated by kingdoms with non-Kshatriya origins; for example, dynasties like the Karkotas trace their lineage to Nagas.

Shaila Bano: Brahmins were definitely present—it’s called the “land of rishis,” after all. But, similar to southern India, society was basically Brahmins and non-Brahmins. The valley was dominated by kingdoms with non-Kshatriya origins; for example, dynasties like the Karkotas trace their lineage to Nagas.

Brahmins were broadly divided into the nobility (ministers, military, and administrative roles) and the priestly class. The merchant class existed but wasn’t very prominent. The Kayastha community dominated local administration, and the Kayatha community included people from Brahmin to Shudra backgrounds. Other artisan communities—barbers, gardeners, potters, goldsmiths—were also present.

Sekhar: Ah, so it’s similar to the medieval south—like the Reddy, Nayaka, and Kakatiya dynasties, which were non-Kshatriya in origin, with Brahmins given administrative positions.

Sekhar: Ah, so it’s similar to the medieval south—like the Reddy, Nayaka, and Kakatiya dynasties, which were non-Kshatriya in origin, with Brahmins given administrative positions.

Shaila Bano: Exactly! And another parallel is among Muslims in the valley: there’s a distinction between Syeds and non-Syeds. Syeds (Ashrafis/Peers) usually claim nobility and priestly status, while the rest are non-Syeds.

Shaila Bano: Exactly! And another parallel is among Muslims in the valley: there’s a distinction between Syeds and non-Syeds. Syeds (Ashrafis/Peers) usually claim nobility and priestly status, while the rest are non-Syeds.

Sekhar: Okay, now it’s clear. Even though I don’t fully grasp the essence of the Syed and non-Syed distinction, I understand—it’s kind of like the Brahmin and non-Brahmin difference among Muslims.

Sekhar: Okay, now it’s clear. Even though I don’t fully grasp the essence of the Syed and non-Syed distinction, I understand—it’s kind of like the Brahmin and non-Brahmin difference among Muslims.

Shaila Bano: We’ll talk about that social division later; right now, let’s stick to Ancient Kashmir.

Shaila Bano: We’ll talk about that social division later; right now, let’s stick to Ancient Kashmir.

Sekhar: So basically, the ancient Kashmiri population was a mix of aboriginal hill tribes (Kiratas, Nishadas, Gandharas), plus tribes from neighboring Tibet. Then came Brahmin migrations, Buddhist influences (which were themselves a mix), followed by Greeks and Yuezhi tribes (the Kushans, from near China and Central Asia), and the Sakas (Iranian nomads). Did I get that right?

Sekhar: So basically, the ancient Kashmiri population was a mix of aboriginal hill tribes (Kiratas, Nishadas, Gandharas), plus tribes from neighboring Tibet. Then came Brahmin migrations, Buddhist influences (which were themselves a mix), followed by Greeks and Yuezhi tribes (the Kushans, from near China and Central Asia), and the Sakas (Iranian nomads). Did I get that right?

Shaila Bano: On a broad level, yes — that sums up the ethnic diversity of Kashmir. And later, during the 14th century, there was also an influx of Sayyids and Sufis from the Arab regions.

Shaila Bano: On a broad level, yes — that sums up the ethnic diversity of Kashmir. And later, during the 14th century, there was also an influx of Sayyids and Sufis from the Arab regions.

Sekhar: That’s a lot of information… but actually a good overview.

Sekhar: That’s a lot of information… but actually a good overview.

Shaila Bano: See, even though the Valley today might be linked with radicalism, political disturbances, wars, or curfews, the common Kashmiri is peace-loving, intelligent, and known for generosity and tameez (manners).

Shaila Bano: See, even though the Valley today might be linked with radicalism, political disturbances, wars, or curfews, the common Kashmiri is peace-loving, intelligent, and known for generosity and tameez (manners).

Sekhar: Okay, okay, I get it — you love Kashmir. I’d also like to understand its politics, but enough of your praise session for now. We’ll save that for later.

Sekhar: Okay, okay, I get it — you love Kashmir. I’d also like to understand its politics, but enough of your praise session for now. We’ll save that for later.

Discover more from The Critilizers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.