![]() Mona: Hey Teja, pass me that pipe.

Mona: Hey Teja, pass me that pipe.

![]() Teja: You don’t usually smoke… what’s going on? You seem stressed.

Teja: You don’t usually smoke… what’s going on? You seem stressed.

![]() Mona: What else can I do? I’m so irritated with my friends’ behavior. You know Tina and Reena, right?

Mona: What else can I do? I’m so irritated with my friends’ behavior. You know Tina and Reena, right?

![]() Teja: Yeah, I remember—they got married into the same house, to two brothers.

Teja: Yeah, I remember—they got married into the same house, to two brothers.

![]() Mona: Exactly. And whenever I go to parties or hang out with them, they just ruin everything with their constant fighting. They keep comparing each other and dragging their family politics into everything. It used to be fun before, but now it’s just exhausting.

Mona: Exactly. And whenever I go to parties or hang out with them, they just ruin everything with their constant fighting. They keep comparing each other and dragging their family politics into everything. It used to be fun before, but now it’s just exhausting.

![]() Teja: Haha, okay, I get it. I actually have a solution for your problem.

Teja: Haha, okay, I get it. I actually have a solution for your problem.

![]() Mona: Oh come on, Teja. You might know a lot of things, but this is not your area of expertise. I’ve already tried everything—I’m done.

Mona: Oh come on, Teja. You might know a lot of things, but this is not your area of expertise. I’ve already tried everything—I’m done.

![]() Teja: Okay, okay, relax. Just hear me out. So in most of these cases, isn’t the mother-in-law usually the common enemy? Instead of your friends constantly comparing and fighting with each other, you just need to create a space where they can come together and vent about their mother-in-law. That way, instead of arguing, they’ll be bonding over gossip—and you love gossip anyway, so you’ll enjoy it too.

Teja: Okay, okay, relax. Just hear me out. So in most of these cases, isn’t the mother-in-law usually the common enemy? Instead of your friends constantly comparing and fighting with each other, you just need to create a space where they can come together and vent about their mother-in-law. That way, instead of arguing, they’ll be bonding over gossip—and you love gossip anyway, so you’ll enjoy it too.

![]() Mona: Hey! That actually sounds like a good idea! This might just work. Not bad, Teja. I feel a little better now. Okay, now let’s move on to our discussion on Dravidian politics. Last time you spoke about Thass and Periyar, mostly about their ideologies. What’s next?

Mona: Hey! That actually sounds like a good idea! This might just work. Not bad, Teja. I feel a little better now. Okay, now let’s move on to our discussion on Dravidian politics. Last time you spoke about Thass and Periyar, mostly about their ideologies. What’s next?

![]() Teja: This time, I want to introduce you to the personalities who played a key role in forming the early Dravidian political associations—P.T. Chettiar, T.M. Nair, and Dr. C. Natesa Mudaliar. Let me explain how I came up with the solution to your friends’ drama. You see, Dr. C. Natesa Mudaliar once brokered peace between P.T. Chettiar and T.M. Nair by redirecting their rivalry toward a common adversary—Brahmins. Even though Chettiar and Nair were both influential, they didn’t get along initially. But once Dr. Mudaliar got them to unite, they played a vital role in forming the South Indian Liberal Federation, which eventually evolved into the Justice Party.

Teja: This time, I want to introduce you to the personalities who played a key role in forming the early Dravidian political associations—P.T. Chettiar, T.M. Nair, and Dr. C. Natesa Mudaliar. Let me explain how I came up with the solution to your friends’ drama. You see, Dr. C. Natesa Mudaliar once brokered peace between P.T. Chettiar and T.M. Nair by redirecting their rivalry toward a common adversary—Brahmins. Even though Chettiar and Nair were both influential, they didn’t get along initially. But once Dr. Mudaliar got them to unite, they played a vital role in forming the South Indian Liberal Federation, which eventually evolved into the Justice Party.

![]() Mona: Ohhh, now I see where your idea came from! Clever. But tell me more—who exactly are these three?

Mona: Ohhh, now I see where your idea came from! Clever. But tell me more—who exactly are these three?

![]() Teja: You already understood the roots of the Dravidian ideology, right? And now you’ve got a basic idea of the Non-Brahmin dissent in South India. In a way, these three people gave that dissent and the Dravidian movement a proper political shape.

Teja: You already understood the roots of the Dravidian ideology, right? And now you’ve got a basic idea of the Non-Brahmin dissent in South India. In a way, these three people gave that dissent and the Dravidian movement a proper political shape.

![]() Mona: Okay, so they were the leaders of the movement.

Mona: Okay, so they were the leaders of the movement.

![]() Teja: Exactly. Let’s start with P.T. Chetty.

Teja: Exactly. Let’s start with P.T. Chetty.

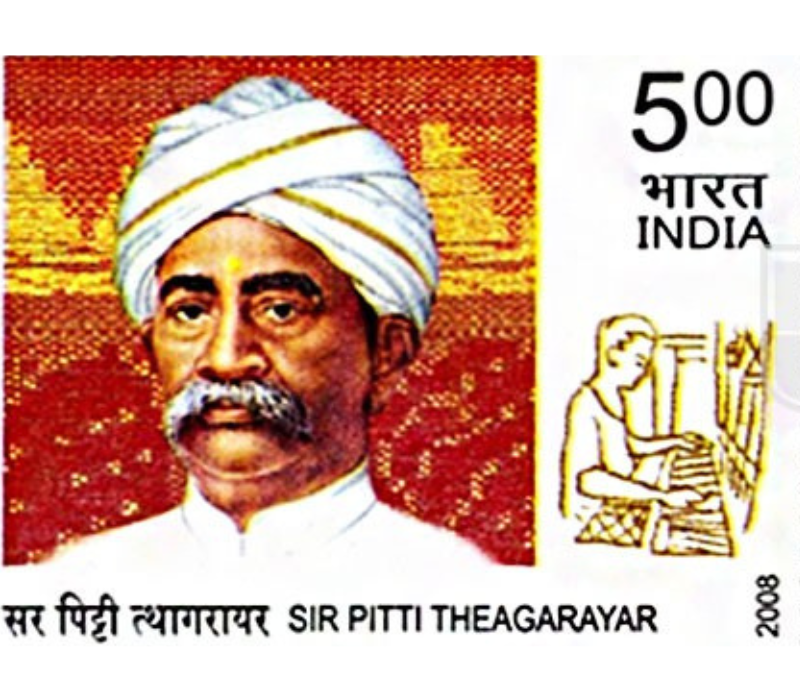

P. Tyagaraya Chettiar:

Dewan Bahadur Pitti Theagaraya Chettiar was born in 1852 into a Devanga family of Telugu origin. A wealthy man with a law degree, he played a crucial role in forming the Justice Party. In fact, he was its first president and led the party until his death in 1925. He was famously called Vellundai Vendar—because of his love for white clothes.

Many South Indian films probably took inspiration from his speeches for their punchy dialogues. He was known for his bold and fearless attitude.

![]() Mona: This is really helping me visualize him. Keep going!

Mona: This is really helping me visualize him. Keep going!

![]() Teja: He was someone who used to issue open challenges. He’d literally say what he was planning to do out loud—even when he knew his enemies (i.e., Brahmins) were nearby and listening. There’s a popular incident where he made such a declaration right in the veranda of the Cosmopolitan Club—loud and clear, just so they could hear it.

Teja: He was someone who used to issue open challenges. He’d literally say what he was planning to do out loud—even when he knew his enemies (i.e., Brahmins) were nearby and listening. There’s a popular incident where he made such a declaration right in the veranda of the Cosmopolitan Club—loud and clear, just so they could hear it.

![]() Mona: That’s like Rajinikanth-style mass entry! Full-on swagger!

Mona: That’s like Rajinikanth-style mass entry! Full-on swagger!

![]() Teja: Exactly! Like I said, his persona could easily have inspired many South Indian hero characters—but he’s the OG. And he wasn’t just all talk. He was wealthy and had access to elite garden parties at the government guest house, but he was ready to skip all that to fight for the cause of a humble tenant or farmer. He was incredibly frank, straightforward, and never played dirty.

Teja: Exactly! Like I said, his persona could easily have inspired many South Indian hero characters—but he’s the OG. And he wasn’t just all talk. He was wealthy and had access to elite garden parties at the government guest house, but he was ready to skip all that to fight for the cause of a humble tenant or farmer. He was incredibly frank, straightforward, and never played dirty.

There’s another instance—he supported the newspaper Indian Patriot and even spent ₹2,000 from his own pocket to defend it in court. And get this—it’s not even clear if he subscribed to the paper! He backed it because it was advocating the same non-Brahmin and Dravidian ideals he stood for. Lord Pentland himself must’ve been a bit shaken when P.T. Chetty won that case!

He was also known for his generosity. He’d help people even when he knew their intentions were questionable, and he’d still go ahead despite warnings from his friends and well-wishers.

![]() Mona: A total man with swag! What a legend.

Mona: A total man with swag! What a legend.

![]() Teja: He was truly pro-masses. He was even open to listening to the younger generation—he’d jokingly say, “Maybe the youngsters are right and I’m wrong!” His house was always buzzing with people, and to everyone in his locality, he was nothing short of a hero or idol. People were even ready to take on the police for him. Like I said, he’s the OG!

Teja: He was truly pro-masses. He was even open to listening to the younger generation—he’d jokingly say, “Maybe the youngsters are right and I’m wrong!” His house was always buzzing with people, and to everyone in his locality, he was nothing short of a hero or idol. People were even ready to take on the police for him. Like I said, he’s the OG!

![]() Mona: So I’m guessing most of his supporters came from Non-Brahmin and Dravidian groups, right?

Mona: So I’m guessing most of his supporters came from Non-Brahmin and Dravidian groups, right?

![]() Teja: While he did strongly campaign for the Non-Brahmin movement, he also had good friends within the Brahmin community. His views weren’t as extreme as Periyar’s. For instance, Brahmin priests used to come to his house for rituals. And when his Non-Brahmin comrades questioned him about that, he’d say that as someone from a wealthy and royal background, it was part of his responsibility to take care of them—even though he didn’t believe in Brahminical ideology. He used to say, “If not here, they’ll just move elsewhere looking for livelihood.” He had a kind of patronizing mindset.

Teja: While he did strongly campaign for the Non-Brahmin movement, he also had good friends within the Brahmin community. His views weren’t as extreme as Periyar’s. For instance, Brahmin priests used to come to his house for rituals. And when his Non-Brahmin comrades questioned him about that, he’d say that as someone from a wealthy and royal background, it was part of his responsibility to take care of them—even though he didn’t believe in Brahminical ideology. He used to say, “If not here, they’ll just move elsewhere looking for livelihood.” He had a kind of patronizing mindset.

Though he was a firm supporter of the Non-Brahmin cause, his focus was more on the political front. When it came to social reforms, he was a bit old-school and leaned towards a more conservative approach.

![]() Mona: I’m getting serious “village head” vibes from him—someone with strong values and morals, who lives by the ideology he believes in.

Mona: I’m getting serious “village head” vibes from him—someone with strong values and morals, who lives by the ideology he believes in.

![]() Teja: That’s a good way to put it. Now let’s move on to the next personality—T.M. Nair.

Teja: That’s a good way to put it. Now let’s move on to the next personality—T.M. Nair.

T.M. Nair:

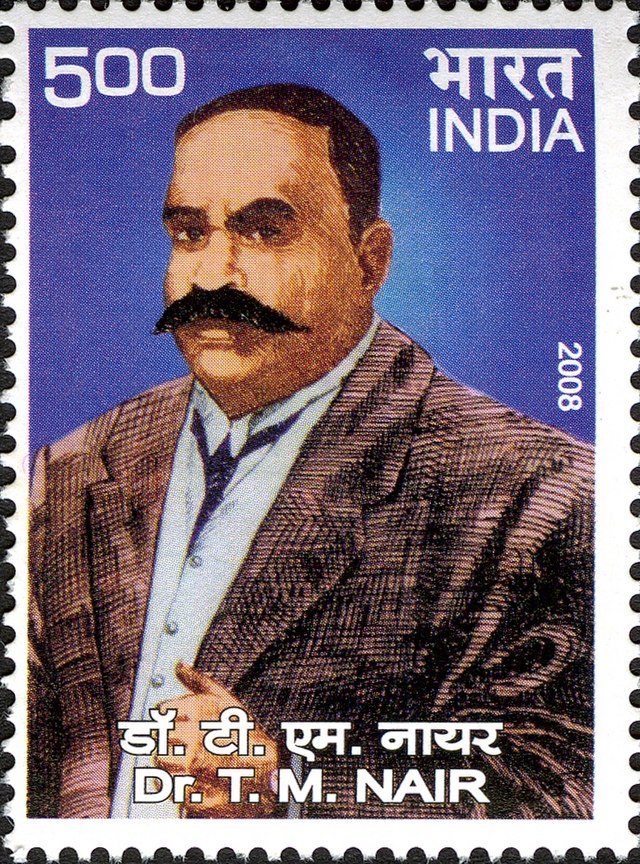

T.M. Nair was born in 1868 into the Taravath family of Palghat (then part of the Madras Presidency). He studied medicine with a specialization in ENT and even did some work on diabetes research. During his time in England, he was quite active—he served as the President of the Edinburgh Indian Association, was a member of the Edinburgh University Liberal Association, and even co-edited the university’s liberal magazine, The Student. For his contributions around the time of World War I, he was awarded the Kaiser-i-Hind medal.

![]() Mona: Wow! So he was in full-on Arjun Reddy mode?

Mona: Wow! So he was in full-on Arjun Reddy mode?

![]() Teja: Haha! More like a fusion of Arjun Reddy and George Reddy—though remember, Arjun Reddy isn’t a political figure. T.M. Nair had the physical presence of a wrestler more than a doctor! He was fluent in English, had a great sense of humor, and enjoyed life—be it food from different cuisines, tobacco, or literature. He would even slip political ideologies subtly into his medical journal(antiseptic) articles. He was also a strong advocate for workers’ rights. Thanks to his efforts, the working hours for laborers were reduced from 17 to 12 hours. Additionally, he served as a member of the Factory Workers Commission during 1907–08.

Teja: Haha! More like a fusion of Arjun Reddy and George Reddy—though remember, Arjun Reddy isn’t a political figure. T.M. Nair had the physical presence of a wrestler more than a doctor! He was fluent in English, had a great sense of humor, and enjoyed life—be it food from different cuisines, tobacco, or literature. He would even slip political ideologies subtly into his medical journal(antiseptic) articles. He was also a strong advocate for workers’ rights. Thanks to his efforts, the working hours for laborers were reduced from 17 to 12 hours. Additionally, he served as a member of the Factory Workers Commission during 1907–08.

There’s an interesting story—apparently, a European woman once mocked him after seeing a photo of him in traditional attire. From that point on, he made sure never to give anyone the chance to ridicule him again. He started dressing impeccably in English suits and spoke with polished elegance. Oh, and he was part of the Egmore Clique.

![]() Mona: Wait, what’s the Egmore Clique?

Mona: Wait, what’s the Egmore Clique?

![]() Teja: If you recall, I told you how, despite being a numerical minority, Brahmins held sway over politics and bureaucracy in the Madras Province. Back in the 1880s, Madras had three major cliques: the Mylapore Clique—dominated by Brahmins (including judges and key political figures), the Egmore Clique—which included non-Brahmin leaders like C. Sankaran Nair (remember Akshay Kumar’s role in Kesari 2?) and T.M. Nair, and the Triplicane Clique—also Brahmin-dominated but with a neutral political stance, featuring people like Subramania Iyer of The Hindu newspaper. The Mylapore Clique was in support of Moderates in Congress party during early 1900’s and so Egmore Clique chose to support extremist faction of the Congress Party initially before Justice party birth

Teja: If you recall, I told you how, despite being a numerical minority, Brahmins held sway over politics and bureaucracy in the Madras Province. Back in the 1880s, Madras had three major cliques: the Mylapore Clique—dominated by Brahmins (including judges and key political figures), the Egmore Clique—which included non-Brahmin leaders like C. Sankaran Nair (remember Akshay Kumar’s role in Kesari 2?) and T.M. Nair, and the Triplicane Clique—also Brahmin-dominated but with a neutral political stance, featuring people like Subramania Iyer of The Hindu newspaper. The Mylapore Clique was in support of Moderates in Congress party during early 1900’s and so Egmore Clique chose to support extremist faction of the Congress Party initially before Justice party birth

![]() Mona: Who exactly were these Moderates and Extremists?

Mona: Who exactly were these Moderates and Extremists?

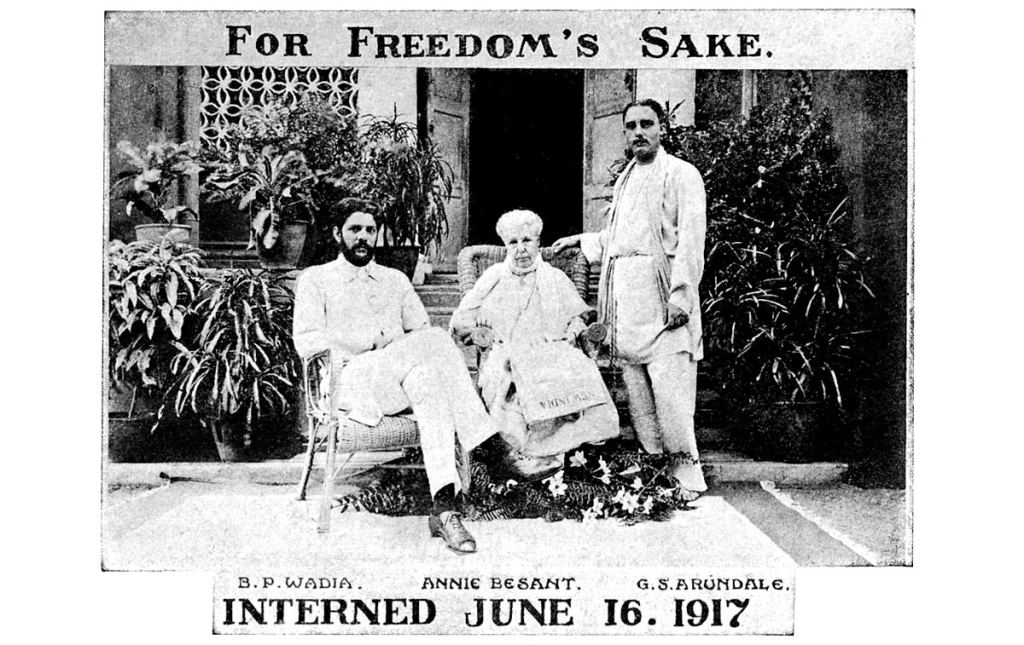

Source: sriaurobindoinstitute.org

![]() Teja: To keep it simple — Moderates (like Dadabhai Naoroji, Gopalakrishna Gokhale, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, G. Subramanya Aiyar, etc.) were those who pushed for political reforms within the framework of British rule. Their tools? Petitions, prayers, and protests — all wrapped nicely within the constitutional setup.

Teja: To keep it simple — Moderates (like Dadabhai Naoroji, Gopalakrishna Gokhale, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, G. Subramanya Aiyar, etc.) were those who pushed for political reforms within the framework of British rule. Their tools? Petitions, prayers, and protests — all wrapped nicely within the constitutional setup.

On the flip side, you had the Extremists — think Lala Lajpat Rai, Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, Aurobindo Ghose, Ashwini Kumar Dutt — who believed in more assertive, direct action. They didn’t want just polite conversations — they were demanding Swarajya (self-rule).

The Extremists often poked fun at the Moderates, branding them as outdated. Aurobindo Ghose even wrote a piece called “New Lamps for Old” — a cheeky jab at their old-school ways.

T.M. Nair was firmly in the Egmore group, and members of this clique played a major role in the Non-Brahmin Movement and the formation of the Justice Party. There was serious rivalry between the Mylapore and Egmore groups—like political gang wars, but for a cause!

![]() Mona: So basically, it was all gangs and cliques—but driven by political purpose!

Mona: So basically, it was all gangs and cliques—but driven by political purpose!

![]() Teja: Hehe, even among the Non-Brahmins in the Madras Corporation Council, there were internal groupings. One group was led by P.T. Chetty, and the other by T.M. Nair. These two didn’t exactly see eye to eye—especially when it came to the water issues related to the Triplicane Tank. Nair wanted the washermen to stop washing clothes in the tank, while P.T. Chetty opposed the move.

Teja: Hehe, even among the Non-Brahmins in the Madras Corporation Council, there were internal groupings. One group was led by P.T. Chetty, and the other by T.M. Nair. These two didn’t exactly see eye to eye—especially when it came to the water issues related to the Triplicane Tank. Nair wanted the washermen to stop washing clothes in the tank, while P.T. Chetty opposed the move.

![]() Mona: Whoa, internal politics too? This just got more interesting.

Mona: Whoa, internal politics too? This just got more interesting.

![]() Teja: Exactly! And remember the Indian Patriot case I told you about earlier? P.T. Chetty and T.M. Nair were on opposite sides of that as well.

Teja: Exactly! And remember the Indian Patriot case I told you about earlier? P.T. Chetty and T.M. Nair were on opposite sides of that as well.

Then came the third key figure—Dr. C. Natesa Mudaliar. He was the peacemaker, the glue that held things together. He managed to unify both P.T. Chetty’s and T.M. Nair’s factions. That’s when the Non-Brahmin movement really started to gain momentum.

Dr. C. Natesa Mudaliar:

He was born in Triplicane, in the Madras Province, and belonged to the Vellalar community. In 1912, he became one of the founders of the Madras United League, an association made up of Non-Brahmin government employees. He also took real initiative by starting hostels for Non-Brahmin boys(Dravidian Home) and went on to establish the Dravidian Association, aiming to strengthen the political influence of Non-Brahmins.

![]() Mona: He definitely sounds like more of a strategist—trying to grow the movement by building institutions and associations.

Mona: He definitely sounds like more of a strategist—trying to grow the movement by building institutions and associations.

![]() Teja: Exactly! In fact, P.T. Chetty didn’t even join the Madras United League until 1912. Later on, the Madras United League was renamed as the Madras Dravidian Association. This association didn’t stop at organizing—it also went into publishing. They released two significant books: Dravidian Worthies (written by Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair—yep, Akshay Kumar’s role in Kesari 2) and Dravidian Non-Brahmin Letters.

Teja: Exactly! In fact, P.T. Chetty didn’t even join the Madras United League until 1912. Later on, the Madras United League was renamed as the Madras Dravidian Association. This association didn’t stop at organizing—it also went into publishing. They released two significant books: Dravidian Worthies (written by Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair—yep, Akshay Kumar’s role in Kesari 2) and Dravidian Non-Brahmin Letters.

These letters were essentially a rallying cry, inviting various Non-Brahmin communities—Reddi, Mudaliar, Naidu, Kamma, and others—to unite under one banner and resist Brahmin domination. Dr. Mudaliar worked to streamline the movement further. He even sent detailed telegrams to London newspapers, and both The London News and The Times published them in their ‘Letters to the Editor’ sections!

![]() Mona: Wow, so what happened once all the differences got ironed out?

Mona: Wow, so what happened once all the differences got ironed out?

![]() Teja: Once the differences were resolved, in 1916, four major Non-Brahmin associations in the Madras Presidency came together to form the South Indian Liberal Federation, which later became widely known as the Justice Party. In November 1916, about 30 prominent Non-Brahmin leaders—including Dr. Natesa Mudaliar, T.M. Nair, P.T. Chetty, the Raja of Panagal, and even the lady Alamelu Manga Tayarammai—gathered at Victoria Public Hall to form SIPA (South Indian People’s Association). This group soon laid the foundation for the South Indian Liberal Federation, with clear political ambitions. The first president of the party was P.T. Chetty.

Teja: Once the differences were resolved, in 1916, four major Non-Brahmin associations in the Madras Presidency came together to form the South Indian Liberal Federation, which later became widely known as the Justice Party. In November 1916, about 30 prominent Non-Brahmin leaders—including Dr. Natesa Mudaliar, T.M. Nair, P.T. Chetty, the Raja of Panagal, and even the lady Alamelu Manga Tayarammai—gathered at Victoria Public Hall to form SIPA (South Indian People’s Association). This group soon laid the foundation for the South Indian Liberal Federation, with clear political ambitions. The first president of the party was P.T. Chetty.

![]() Mona: So, finally the Dravidian ideology got its political form?

Mona: So, finally the Dravidian ideology got its political form?

![]() Teja: Exactly! And these three leaders were absolutely key to the formation of the party. Not just that—they also launched a newspaper called Justice in 1917 to take their ideology to the masses. It became so popular that people started referring to the South Indian Liberal Federation simply as the Justice Party.

Teja: Exactly! And these three leaders were absolutely key to the formation of the party. Not just that—they also launched a newspaper called Justice in 1917 to take their ideology to the masses. It became so popular that people started referring to the South Indian Liberal Federation simply as the Justice Party.

![]() Mona: Now it’s all coming together for me—the core ideology of dissent and the leaders who transformed it into a political movement.

Mona: Now it’s all coming together for me—the core ideology of dissent and the leaders who transformed it into a political movement.

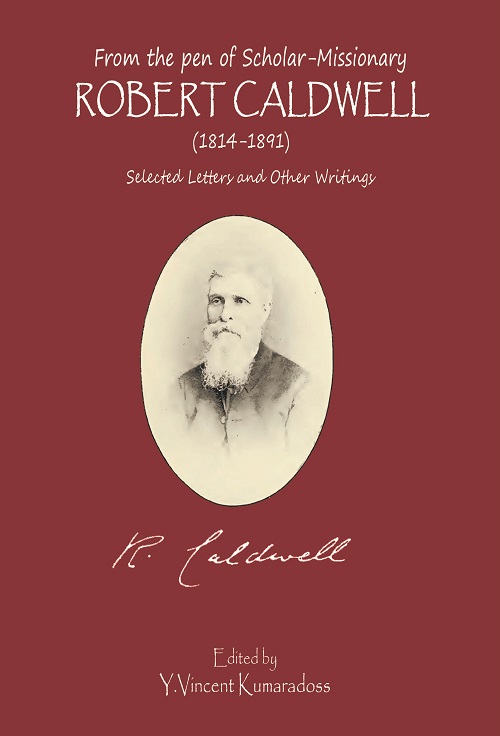

![]() Teja: One more thing worth noting—newspapers and print media were crucial in spreading any ideology during that time. Many Non-Brahmin leaders often referred to the works of Robert Caldwell, a missionary and anthropologist. His writings provided ideological support for the anti-Brahmin stance. His anthropological study of the local Nadar population and his well-known book A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South Indian Family of Languages were frequently cited by Non-Brahmin intellectuals and activists.

Teja: One more thing worth noting—newspapers and print media were crucial in spreading any ideology during that time. Many Non-Brahmin leaders often referred to the works of Robert Caldwell, a missionary and anthropologist. His writings provided ideological support for the anti-Brahmin stance. His anthropological study of the local Nadar population and his well-known book A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South Indian Family of Languages were frequently cited by Non-Brahmin intellectuals and activists.

![]() Mona: So in a way, even the missionaries were indirectly supporting the Dravidian ideology? And can we say that the Non-Brahmins felt the Congress Party wasn’t representing their interests, so they started their own party?

Mona: So in a way, even the missionaries were indirectly supporting the Dravidian ideology? And can we say that the Non-Brahmins felt the Congress Party wasn’t representing their interests, so they started their own party?

![]() Teja: Caldwell, though a missionary, was primarily a noted anthropologist—so missionary support was kind of ambiguous. But yes, the Non-Brahmin leaders often believed that Congress was essentially a Brahmin-Baniya party (sometimes including Rajputs too). Justice Party leaders were frequently seen siding with British policies. By 1916, the Congress Party managed to resolve its internal rift between the Extremists (Nationalists) and Moderates, and began working more unitedly towards the freedom movement. However, the Justice Party deliberately chose to stay away and not align with Congress.

Teja: Caldwell, though a missionary, was primarily a noted anthropologist—so missionary support was kind of ambiguous. But yes, the Non-Brahmin leaders often believed that Congress was essentially a Brahmin-Baniya party (sometimes including Rajputs too). Justice Party leaders were frequently seen siding with British policies. By 1916, the Congress Party managed to resolve its internal rift between the Extremists (Nationalists) and Moderates, and began working more unitedly towards the freedom movement. However, the Justice Party deliberately chose to stay away and not align with Congress.

For example, the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms were rejected by the Congress, but leaders of the Justice Party had a more moderate take—they felt Montague should be given a chance. Similarly, the Home Rule Movement being led by Annie Besant in the Madras Province wasn’t supported by Justice Party leaders. All of this added to their image of being pro-British.

![]() Mona: Okay, okay—I get that you know a lot. But help me understand the background of the Home Rule Movement and the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms.

Mona: Okay, okay—I get that you know a lot. But help me understand the background of the Home Rule Movement and the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms.

![]() Teja: Sure. So, around 1916, as part of the freedom struggle, Annie Besant(Madras) and Bal Gangadhar Tilak launched the Home Rule Movement, demanding self-rule—inspired by similar efforts in Ireland. Annie Besant was a Theosophist, and Theosophical beliefs often glorified Vedic and Brahminical traditions of the land. (Not diving too deep into that, just giving you context.)

Teja: Sure. So, around 1916, as part of the freedom struggle, Annie Besant(Madras) and Bal Gangadhar Tilak launched the Home Rule Movement, demanding self-rule—inspired by similar efforts in Ireland. Annie Besant was a Theosophist, and Theosophical beliefs often glorified Vedic and Brahminical traditions of the land. (Not diving too deep into that, just giving you context.)

The Non-Brahmin leaders feared that if Annie Besant succeeded in pushing through her reforms, it would only strengthen Brahmin dominance in Indian politics. Congress backed Annie’s movement, but T.M. Nair even fought a legal case against the Home Rule leaders. The Non-Brahmin leaders felt it was essential for their communities to unite and counter this movement.

![]() Mona: Got it! Now tell me—what exactly were the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms about?

Mona: Got it! Now tell me—what exactly were the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms about?

![]() Teja: In return for India’s support to the British during World War I, the British promised to implement reforms that would grant provincial autonomy—basically allowing provinces more power to make their own laws. But they also introduced a system of dyarchy, where the most important legislative subjects remained under British control.

Teja: In return for India’s support to the British during World War I, the British promised to implement reforms that would grant provincial autonomy—basically allowing provinces more power to make their own laws. But they also introduced a system of dyarchy, where the most important legislative subjects remained under British control.

This arrangement wasn’t welcomed by Congress or the freedom movement leaders—Congress boycotted the elections held under these reforms. But the Justice Party contested and won, eventually forming the government. We can dive deeper into the Justice Party later. There’s more to the Montague-Chelmsford reforms, but a lot of it isn’t relevant for our current discussion.

![]() Mona: So basically, they seemed to oppose anything Congress supported and went against anything that had Brahmin backing. But still, the resistance against the Montague reforms seems like something they should’ve supported, no?

Mona: So basically, they seemed to oppose anything Congress supported and went against anything that had Brahmin backing. But still, the resistance against the Montague reforms seems like something they should’ve supported, no?

![]() Teja: True. While the movement started with the aim of opposing caste dominance, it didn’t fully evolve in that direction. It didn’t do much for Dalit upliftment or emancipation, though it did introduce reservations for Non-Brahmin castes. In reality, it mostly empowered the already dominant Non-Brahmin castes politically.

Teja: True. While the movement started with the aim of opposing caste dominance, it didn’t fully evolve in that direction. It didn’t do much for Dalit upliftment or emancipation, though it did introduce reservations for Non-Brahmin castes. In reality, it mostly empowered the already dominant Non-Brahmin castes politically.

However, it did succeed in instilling a sense of Dravidian pride and encouraging the growth of Dravidian literature. Though leaders insisted they were against Brahminism and not Brahmins, their rhetoric led to growing anti-Brahmin sentiment among Non-Brahmin masses in the South.

![]() Mona: So it began by opposing caste-based oppression by Brahminical castes, but ended up representing the interests of dominant Non-Brahmin castes—like the Reddis, Chettiars, Mudaliyars, Kammas, and Nairs. Feels like it leaned more toward caste representation and building a Dravidian identity, rather than actual annihilation of caste.

Mona: So it began by opposing caste-based oppression by Brahminical castes, but ended up representing the interests of dominant Non-Brahmin castes—like the Reddis, Chettiars, Mudaliyars, Kammas, and Nairs. Feels like it leaned more toward caste representation and building a Dravidian identity, rather than actual annihilation of caste.

![]() Teja: That’s a fair point. Even within the same party, you’ll find a mix—some leaders were moderates, some extremists, and of course, some outliers too. My aim was to give you different angles from various leaders and their ideologies.

Teja: That’s a fair point. Even within the same party, you’ll find a mix—some leaders were moderates, some extremists, and of course, some outliers too. My aim was to give you different angles from various leaders and their ideologies.

Next, we’ll explore the Justice Party, its transformations, and the other key political figures who played a role in shaping the movement.

![]() Mona: Okay, now I’m finally starting to connect the dots. This is way more complex than I initially thought! Let me process all of this first—then we’ll party!

Mona: Okay, now I’m finally starting to connect the dots. This is way more complex than I initially thought! Let me process all of this first—then we’ll party!

Discover more from The Critilizers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.