Sekhar: Shaila, thanks to your over-excitement, we’ve reached the airport way too early! Now I have no idea how to kill time. Okay then, why don’t you tell me something about your Kashmir?

Sekhar: Shaila, thanks to your over-excitement, we’ve reached the airport way too early! Now I have no idea how to kill time. Okay then, why don’t you tell me something about your Kashmir?

Shaila Bano: Excuse me? Kashmir is not a time-pass — it’s my jaan! If you’re going to take it casually, I’m not telling you anything.

Shaila Bano: Excuse me? Kashmir is not a time-pass — it’s my jaan! If you’re going to take it casually, I’m not telling you anything.

Sekhar: Okay, ma’am! I’m not undermining your sentiments. It’s just that, since we were already discussing Kashmir earlier, and now we have time to spare, I thought you could tell me more about it.

Sekhar: Okay, ma’am! I’m not undermining your sentiments. It’s just that, since we were already discussing Kashmir earlier, and now we have time to spare, I thought you could tell me more about it.

Shaila Bano: Hmm, alright. Last time I spoke about ancient Kashmiri culture, society, and faiths — do you want me to continue from there?

Shaila Bano: Hmm, alright. Last time I spoke about ancient Kashmiri culture, society, and faiths — do you want me to continue from there?

Sekhar: We can talk about that later, but for now, can you tell me about the insurgency and disturbances in Kashmir? It’s always in the news, but the information we get is in bits and pieces — it’s hard to understand the full picture.

Sekhar: We can talk about that later, but for now, can you tell me about the insurgency and disturbances in Kashmir? It’s always in the news, but the information we get is in bits and pieces — it’s hard to understand the full picture.

Shaila Bano: That’s a huge topic — but yes, we have time. Let me try to give you a decent understanding of it, and we’ll explore it more deeply during our journey.

Shaila Bano: That’s a huge topic — but yes, we have time. Let me try to give you a decent understanding of it, and we’ll explore it more deeply during our journey.

Sekhar: Great, then start from the beginning — why did such a peaceful region get disturbed in the first place?

Sekhar: Great, then start from the beginning — why did such a peaceful region get disturbed in the first place?

Shaila Bano: To understand the origins, we need to look at the period around the Independence movement. Everyone knows that along with Independence, India also witnessed the deep scars of Partition.

Shaila Bano: To understand the origins, we need to look at the period around the Independence movement. Everyone knows that along with Independence, India also witnessed the deep scars of Partition.

The Beginnings:

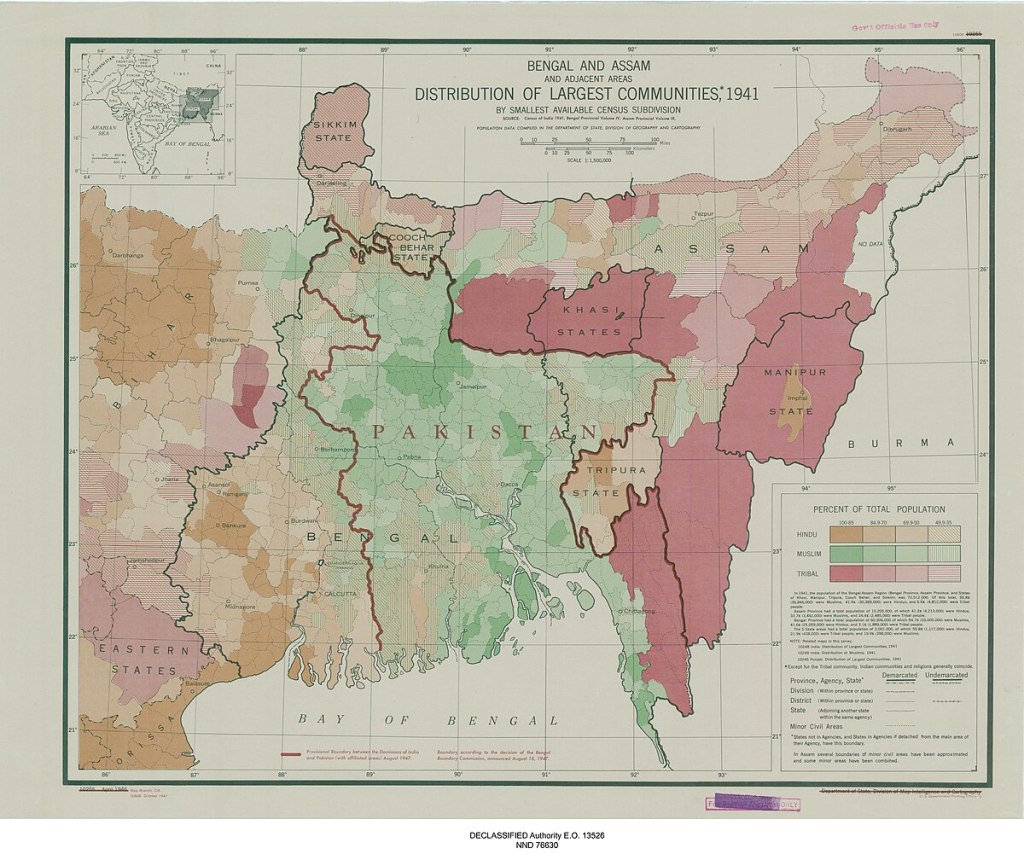

Even though the seeds of communalism were sown long before, the British actively nurtured communal sentiments over time — whether through the Partition of Bengal (1905) or the Morley-Minto Reforms introducing communal electorates.

The 1920s witnessed a sharp rise in communal feelings among both Hindu and Muslim communities. The RSS and Hindu Mahasabha were formed, while the Muslim League became an active political organization. Even though the Congress took the center stage in national politics, communal sentiments continued to gain traction underneath.

Sekhar: Okay, so it’s like these communal tensions kept growing and eventually led to the Partition of the country in 1947?

Sekhar: Okay, so it’s like these communal tensions kept growing and eventually led to the Partition of the country in 1947?

Shaila Bano: Yes. Historian Bipin Chandra classifies Indian communalism into three phases.

Shaila Bano: Yes. Historian Bipin Chandra classifies Indian communalism into three phases.

1st Phase: The recognition that there are two distinct communities in India — Hindus and Muslims. This was the phase of communal consciousness. It began around the Partition of Bengal in 1905, which was done on communal rather than administrative lines. Some historians trace this phase even earlier, citing Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s ideas and the Aligarh Movement. But let’s not dive too deep into that debate.

2nd Phase: The belief that Hindus and Muslims are two distinct communities with different political interests — but they can still coexist despite these differences. This phase unfolded in the 1920s, after the Non-Cooperation and Khilafat Movements, when political organizations on both sides began asserting their demands more clearly.

3rd Phase: This is when the narrative hardened — that Hindus and Muslims were fundamentally different nations with no common ground and therefore could not coexist. This phase saw the demand for a separate nation, culminating in violent events like the Direct Action Day, which eventually led to Partition. Although both sides had extremists, the Muslim League, led by Jinnah, managed to popularize this ideology effectively among sections of the population, deeply disturbing the social fabric.

Sekhar: So, in simple terms, it was extreme communal ideology fueled by political forces — starting from people’s demands and ending in separatism. For example, though it’s not the same, I’d compare it to how Telangana was formed — it started as a movement for representation and ended up as a separate state. I’ve used all the big words I could pick up, and I think I’ve exhausted my brain, so please don’t mock me if I’m wrong!

Sekhar: So, in simple terms, it was extreme communal ideology fueled by political forces — starting from people’s demands and ending in separatism. For example, though it’s not the same, I’d compare it to how Telangana was formed — it started as a movement for representation and ended up as a separate state. I’ve used all the big words I could pick up, and I think I’ve exhausted my brain, so please don’t mock me if I’m wrong!

Shaila Bano: Jaana (mockingly), I’m actually impressed by your effort — but, as always, I’ll have to correct you. You know I love correcting you!

Shaila Bano: Jaana (mockingly), I’m actually impressed by your effort — but, as always, I’ll have to correct you. You know I love correcting you!

It’s fine to understand the third phase in that way, but drawing a parallel with Telangana isn’t quite accurate. Let me simplify it for you. Whenever an idea enters the political or public sphere, it usually gets the suffix “–ism.” For example:

- The feeling of caste becomes casteism,

- The feeling of region becomes regionalism,

- The language issue becomes linguistic nationalism,

- And similarly, communal feelings become communalism.

The demand for Telangana falls within the constitutional sphere — it was a democratic movement, not an extremist one. Extremist tendencies, on the other hand, lead to phenomena like separatism (for instance, the demand for a separate Dravidistan to drive out Brahminical influence), or religious fundamentalism, which often takes violent forms.

Sekhar: So you’re saying Kashmir was also affected by that third phase of communalism during Partition, and that’s why the disturbances are still continuing in the Valley?

Sekhar: So you’re saying Kashmir was also affected by that third phase of communalism during Partition, and that’s why the disturbances are still continuing in the Valley?

Shaila Bano: To your surprise — no! The communal activity was actually much stronger in other parts of the subcontinent than in Kashmir. In fact, there was a towering figure named Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (known as the Frontier Gandhi) from the North-West Frontier Province, who was completely against Partition itself.

Shaila Bano: To your surprise — no! The communal activity was actually much stronger in other parts of the subcontinent than in Kashmir. In fact, there was a towering figure named Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (known as the Frontier Gandhi) from the North-West Frontier Province, who was completely against Partition itself.

Sekhar: Then how did all these extremist activities and disturbances begin in Kashmir?

Sekhar: Then how did all these extremist activities and disturbances begin in Kashmir?

Shaila Bano: Ah, let me tell you the actual story.

Shaila Bano: Ah, let me tell you the actual story.

The person who coined the term “Pakistan” was Choudhary Rahmat Ali, a Muslim nationalist activist. He introduced it in his pamphlet “Now or Never”, where “Pakistan” referred to Muslim-majority regions in the northwestern part of the subcontinent. Interestingly, the letter “K” in PAK stood for Kashmir.

Later, the term took on a life of its own — people began interpreting it more poetically. The word “Pak” in Persian and Urdu means spiritually pure and clean, and poets like Mohammad Iqbal (yes, the same man who wrote “Sare Jahan Se Achha”) further romanticized the idea.

(Note: Although Iqbal shared similar ideas, the conceptualization was actually done by Choudhary Rahmat Ali. Initially, his idea wasn’t taken too seriously in political circles since he was just a student at the time, but it gradually gained traction and political weight by the 1940s.)

Sekhar: Okay, now I get it. But after Partition, Kashmir became part of India — so obviously Pakistan wouldn’t have welcomed that, which must have been the root cause of the disturbances.

Sekhar: Okay, now I get it. But after Partition, Kashmir became part of India — so obviously Pakistan wouldn’t have welcomed that, which must have been the root cause of the disturbances.

Shaila Bano: Exactly. Initially, people genuinely wanted to resolve the issue peacefully — especially after the trauma of Partition. But Pakistan didn’t allow that. It even tried to meddle politically in the princely states of Junagadh and Hyderabad.

Shaila Bano: Exactly. Initially, people genuinely wanted to resolve the issue peacefully — especially after the trauma of Partition. But Pakistan didn’t allow that. It even tried to meddle politically in the princely states of Junagadh and Hyderabad.

Moreover, in 1948, it sent lashkars (in the guise of tribal fighters) to capture Kashmir. Eventually, Maharaja Hari Singh, the then ruler of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, signed the Instrument of Accession with India. I won’t go into all the details right now, but in short — after Partition, a portion of Kashmir came under Pakistan’s control (POK), and later, Pakistan even gave a small part of it to its all-time friend, China.

Sekhar: Wait — whose land are they donating? That’s like gifting someone else’s property! So, from that time onward, the Valley has been facing disturbances?

Sekhar: Wait — whose land are they donating? That’s like gifting someone else’s property! So, from that time onward, the Valley has been facing disturbances?

Shaila Bano: Not exactly. The secessionist movements and religious fundamentalism weren’t that active in the Valley initially. And not to boast, but Kashmiris are genuinely peace-loving people.

Shaila Bano: Not exactly. The secessionist movements and religious fundamentalism weren’t that active in the Valley initially. And not to boast, but Kashmiris are genuinely peace-loving people.

There are, however, several dimensions to the insurgency in Kashmir. Let’s try to connect the dots to understand what’s actually going on.

Sekhar: One thing I do understand is Pakistan’s role — through its unofficial armed segments — starting right from 1948, as you mentioned.

Sekhar: One thing I do understand is Pakistan’s role — through its unofficial armed segments — starting right from 1948, as you mentioned.

Shaila Bano: Correct. Let me simplify this for you.

Shaila Bano: Correct. Let me simplify this for you.

The strategic culture — meaning the core military belief — of the Pakistani Army is that Kashmir is an integral part of Pakistan. So whenever a democratically elected government in Pakistan tries to make peace or reach a truce with India, the army steps in.

That’s why, time and again, we’ve seen military coups in Pakistan — the army taking over from civilian governments whenever peace with India seems possible. you can even see Pakistani Army General is addressing in few international events .

Sekhar: Yes, even the recent elections in Pakistan were just an eyewash. Eventually, someone favorable to the army and the ISI ends up forming the government. It’s like a kind of feudal and elite rule that still continues in Pakistan, even though it calls itself a democracy and a republic. Now I can see why it struggles with poverty and poor macroeconomic indicators.

Sekhar: Yes, even the recent elections in Pakistan were just an eyewash. Eventually, someone favorable to the army and the ISI ends up forming the government. It’s like a kind of feudal and elite rule that still continues in Pakistan, even though it calls itself a democracy and a republic. Now I can see why it struggles with poverty and poor macroeconomic indicators.

Shaila Bano: OMG! You’re actually following international news, not just national news?

Shaila Bano: OMG! You’re actually following international news, not just national news?

Sekhar: Hehe, most of my knowledge comes from social media — I just borrowed some lines and used them here. Please continue!

Sekhar: Hehe, most of my knowledge comes from social media — I just borrowed some lines and used them here. Please continue!

Shaila Bano: Alright, so despite Pakistan’s strong strategic beliefs, it has never been able to defeat India militarily. It lost in 1965, and 1971 was the year when East Pakistan separated to become Bangladesh.

Shaila Bano: Alright, so despite Pakistan’s strong strategic beliefs, it has never been able to defeat India militarily. It lost in 1965, and 1971 was the year when East Pakistan separated to become Bangladesh.

After that, Pakistan began relying on non-state actors to nurture anti-India sentiments in Kashmir. These elements are still active — not only in the Valley but also in other sensitive regions. Even as early as 1947, organizations like the Plebiscite Front were working to keep secessionist ideas alive.

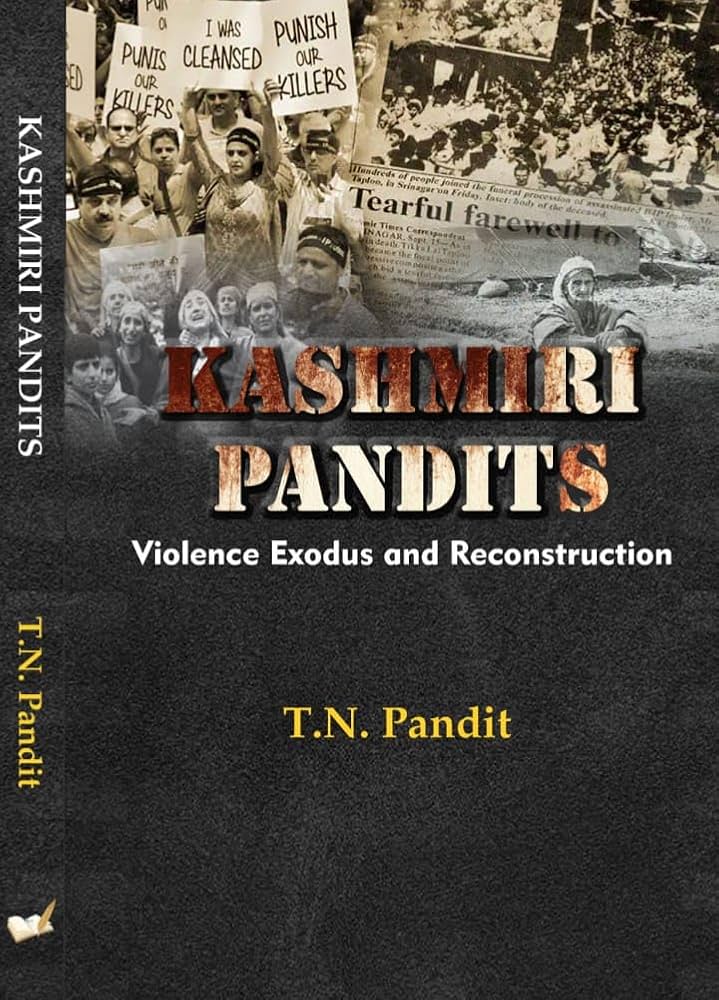

Sekhar: So, it’s like — once these sentiments were successfully nurtured into extremist tendencies, they eventually led to acts of violence. For example, the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits.

Sekhar: So, it’s like — once these sentiments were successfully nurtured into extremist tendencies, they eventually led to acts of violence. For example, the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits.

Shaila Bano: Let me add a few more points before you jump to any sort of concrete conclusion. If you recall, during the Cold War era, Pakistan was part of NATO’s CENTO alliance and was an ally of the USA.

Shaila Bano: Let me add a few more points before you jump to any sort of concrete conclusion. If you recall, during the Cold War era, Pakistan was part of NATO’s CENTO alliance and was an ally of the USA.

That rivalry extended into Afghanistan — with the Soviet Union supporting the ruling authority and the USA backing the dissenting factions through Pakistan. The group Jamaat-e-Islami Afghanistan (one of the major Mujahideen factions) was founded by Burhanuddin Rabbani and was inspired by Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan.

Sekhar: Girl, why did you suddenly jump to Afghanistan? Did you forget what we were talking about? I think age is catching up — we were discussing Kashmir!

Sekhar: Girl, why did you suddenly jump to Afghanistan? Did you forget what we were talking about? I think age is catching up — we were discussing Kashmir!

Shaila Bano: Patience! I know exactly what I’m talking about — now shut up and listen! The point I’m making is that the factions supported by the USA were trained in Pakistan (taalim was given there). They received both spiritual and military training — and it’s said that scholars from Saudi Arabia were invited to give lectures (though those scholars might not have had the full picture).

Shaila Bano: Patience! I know exactly what I’m talking about — now shut up and listen! The point I’m making is that the factions supported by the USA were trained in Pakistan (taalim was given there). They received both spiritual and military training — and it’s said that scholars from Saudi Arabia were invited to give lectures (though those scholars might not have had the full picture).

During this time, radical and fundamentalist ideologies were taught. The trainees were told that if Afghanistan were ruled by a communist-backed government, Islam would be in danger. And that’s where the narrative “Islam is in danger” actually began.

After their training, these fighters were sent back to Afghanistan — but a few students stayed behind in Pakistan. The word “Talib” means student, and that’s how the term Taliban came into existence.

Sekhar: Okay… now I get it! So that’s how the Taliban started. But I still don’t see the connection to Kashmir.

Sekhar: Okay… now I get it! So that’s how the Taliban started. But I still don’t see the connection to Kashmir.

Shaila Bano: Patience, Mr. Impatient! Jamaat-e-Islami is also active in Kashmir. In fact, it was a banned organization under the UAPA. But don’t confuse it with Jamaat-e-Islami Hind (JIH) — that’s the Indian branch, which mainly functions as a religious organization.

Shaila Bano: Patience, Mr. Impatient! Jamaat-e-Islami is also active in Kashmir. In fact, it was a banned organization under the UAPA. But don’t confuse it with Jamaat-e-Islami Hind (JIH) — that’s the Indian branch, which mainly functions as a religious organization.

After Independence, in 1952, Jamaat-e-Islami Hind decided to separate its Kashmiri branch because of the region’s disputed status. Let’s not go deep into Jamat -e -Islami and its origins right now — that’s another long story.

Sekhar: This is actually quite interesting! JEM has operational branches in several parts of the world. Its role really depends on the leadership at the time — in some places, it sticks strictly to religious aspects, while in others, it’s been misused for different purposes like narrative building, nurturing sentiments, and so on.

Sekhar: This is actually quite interesting! JEM has operational branches in several parts of the world. Its role really depends on the leadership at the time — in some places, it sticks strictly to religious aspects, while in others, it’s been misused for different purposes like narrative building, nurturing sentiments, and so on.

Shaila Bano: Let’s keep JEM aside for now. The main point I was getting to is this — after Soviet Russia withdrew from Afghanistan and the USSR eventually collapsed, the USA also pulled out, without keeping its promises.

Shaila Bano: Let’s keep JEM aside for now. The main point I was getting to is this — after Soviet Russia withdrew from Afghanistan and the USSR eventually collapsed, the USA also pulled out, without keeping its promises.

They left the trained rebels behind without teaching them how to establish a democratic government — and they failed to fulfill several other promises as well. This created unrest among the young rebels, who later formed organizations like Al-Qaeda. (Events like 9/11 are a result of that — but we’ll talk about that later.)

Now, Pakistan saw an opportunity to use the remaining faction of the Taliban to create unrest in Kashmir. It infiltrated these fighters into POK and gradually into Kashmir and other regions too. These were often referred to as “Mehmaan Taliban” — meaning guest Taliban. (They weren’t Afghan-backed; they were Pakistan-backed militants who stayed behind. So, the term “Mehmaan Taliban” isn’t officially used, but it fits the description.)

Sekhar: OMG! So you’re saying the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan happened in 1989, and the Kashmiri Pandit exodus took place in 1990 — which means there was also a foreign militant angle to that violence?

Sekhar: OMG! So you’re saying the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan happened in 1989, and the Kashmiri Pandit exodus took place in 1990 — which means there was also a foreign militant angle to that violence?

Shaila Bano: Exactly, yes. I mean, how else do you think the extremists in the Valley got access to arms? It’s believed that militants were equipped with Kalashnikovs and had even more weapons than the Jammu and Kashmir Police at one point.

Shaila Bano: Exactly, yes. I mean, how else do you think the extremists in the Valley got access to arms? It’s believed that militants were equipped with Kalashnikovs and had even more weapons than the Jammu and Kashmir Police at one point.

Sekhar: Now I’m beginning to connect the dots — though it’s definitely not simple! There’s so much happening all at once.

Sekhar: Now I’m beginning to connect the dots — though it’s definitely not simple! There’s so much happening all at once.

Shaila Bano: Right, and there’s another important event from that period — the allegedly rigged elections, which created strong public dissent against both the Central and State Governments. Those sentiments were further nurtured by fringe elements, who cleverly fueled anger and distrust.

Shaila Bano: Right, and there’s another important event from that period — the allegedly rigged elections, which created strong public dissent against both the Central and State Governments. Those sentiments were further nurtured by fringe elements, who cleverly fueled anger and distrust.

This environment made it easier for extremist groups to manipulate public opinion — portraying the Hindu Pandit population as agents of the Central Government. That narrative deepened the fault lines between the two communities.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Kashmir was actually flooded with tourists from all over the world. It truly was a Jannat — a paradise — that was slowly turned gloomy.

Sekhar: It’s really sad to think that people got consumed by such communal hatred.

Sekhar: It’s really sad to think that people got consumed by such communal hatred.

Shaila Bano: Let me give you an example — before the Kashmiri Pandit issue, there were also the Sikh riots and the rise of the Khalistan movement. But the Sikh community soon realized that the movement was being supported by Pakistan and other fringe groups who wanted to benefit from deepening that fault line. That’s why it couldn’t persist strongly.

Shaila Bano: Let me give you an example — before the Kashmiri Pandit issue, there were also the Sikh riots and the rise of the Khalistan movement. But the Sikh community soon realized that the movement was being supported by Pakistan and other fringe groups who wanted to benefit from deepening that fault line. That’s why it couldn’t persist strongly.

Sekhar: Yes, now I remember — that phase was really tough for the entire country. Even the South saw the rise of organizations like the LTTE, and that too caused serious unrest.

Sekhar: Yes, now I remember — that phase was really tough for the entire country. Even the South saw the rise of organizations like the LTTE, and that too caused serious unrest.

Shaila Bano: One major reason for targeting the Kashmiri Pandit population was that by driving them out violently, the extremists hoped to create a partition-like atmosphere — something that could make it easier to “capture” the Valley completely. But thankfully, that didn’t happen.

Shaila Bano: One major reason for targeting the Kashmiri Pandit population was that by driving them out violently, the extremists hoped to create a partition-like atmosphere — something that could make it easier to “capture” the Valley completely. But thankfully, that didn’t happen.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, the Valley witnessed a massive militant phase. There were large-scale recruitments, and several organizations like Jaish-e-Mohammed, Indian Mujahideen, and others came up.

Unemployed youth were the prime targets. While the rest of the country was benefiting from liberalization and privatization reforms, the youth in the Valley — still heavily dependent on the government for jobs — were fed narratives of fundamentalism and militancy. This pushed the Valley back by nearly 50 years.

That period also saw the growth of madrasas and related activities, which became breeding grounds for radical ideologies. madrasa as a institution is not radical, it is a place where religious education is given, The name of madrasa was misused and radical seeds are sown.

Sekhar: Now I finally understand what radicalization really means. But what kind of narratives were these people being fed?

Sekhar: Now I finally understand what radicalization really means. But what kind of narratives were these people being fed?

Shaila Bano: There’s actually a spectrum of ideologies that existed — and still do.

Shaila Bano: There’s actually a spectrum of ideologies that existed — and still do.

The first faction was the radical pro-Pakistan group. They were fed dreams of a “pure land” — Pak land — and the romanticized idea of Pakistan and Islam. But in reality, Pakistan couldn’t even address the concerns of its own people. Its governance was (and still is) extremely poor, democratic rights are constantly compromised, and the people’s mandate is often overturned.

The second faction believed in the idea of an independent Kashmir. They were told that both Kashmiri culture and Islam were in danger, and that the Central Government treated Kashmiris like stepbrothers.

In truth, though, Kashmir has always had a diverse and syncretic culture. The government at that time could have countered these false narratives through a “winning hearts and minds” approach — but unfortunately, they failed to do so.

The third and largest faction comprised Common Muslims (Common man) — people who simply wanted good governance and social harmony. But since they were of no use to fringe groups, they were often ignored — and some even suffered during the Kashmiri Pandit exodus.

The extremists’ main goal was to spread their ideology and gradually pull as many people as possible from this majority group into the first two folds.

Sekhar: Dude, there’s a lot going on — it’s so complex! I can only imagine how a common Kashmiri must have felt, constantly bombarded with conflicting narratives while struggling with unemployment, poverty, and even basic issues like electricity. He probably wouldn’t even know who to blame or where to go for grievance redressal. What about the local government, though?

Sekhar: Dude, there’s a lot going on — it’s so complex! I can only imagine how a common Kashmiri must have felt, constantly bombarded with conflicting narratives while struggling with unemployment, poverty, and even basic issues like electricity. He probably wouldn’t even know who to blame or where to go for grievance redressal. What about the local government, though?

Shaila Bano: The local government? Completely elitist. The politicians filled the bureaucracy with their own people — those who’d do their bidding. Honest bureaucrats were often transferred, and if any of them happened to belong to the upper castes, their actions were politicized.

Shaila Bano: The local government? Completely elitist. The politicians filled the bureaucracy with their own people — those who’d do their bidding. Honest bureaucrats were often transferred, and if any of them happened to belong to the upper castes, their actions were politicized.

Even university hirings were done in the same biased way. For them, the only thing that truly mattered was “Gupkar Road networking.” They wouldn’t even let outside officials do their jobs transparently.

And to make matters worse, there’s the constant presence of the army and geo-political meddling from the other side. It’s a complicated .

Sekhar: One thing’s for sure — kudos to those Kashmiris who still managed to excel in their fields despite all this chaos!

Sekhar: One thing’s for sure — kudos to those Kashmiris who still managed to excel in their fields despite all this chaos!

Shaila Bano: Absolutely. And not just that — even Islamic shrines weren’t spared. In 1995, the shrine of Nuruddin (Nund Rishi) was destroyed in the name of purist Islam.

Shaila Bano: Absolutely. And not just that — even Islamic shrines weren’t spared. In 1995, the shrine of Nuruddin (Nund Rishi) was destroyed in the name of purist Islam.

No matter how orthodox a follower of Islam might be — they may not visit or worship at a shrine, but they would never disrespect a Sufi saint. (Of course, there are internal differences among Sufi sects too.)

These acts were deliberately carried out to show that divisions existed — to portray the Valley as communal and deeply divided along religious lines. The same techniques used elsewhere in the world to create conflict were now being replicated in Kashmir.

And as always — it’s the common people of Kashmir who suffered the most.

Sekhar: Oh, now I get it — the recent Pahalgam incident was just another attempt to sustain that rift, wasn’t it?

Sekhar: Oh, now I get it — the recent Pahalgam incident was just another attempt to sustain that rift, wasn’t it?

Shaila Bano: Exactly. That attack was meant to strike at the very core of the Indian belief that Hindus and Muslims can live peacefully together — especially when something like this happens on such a large tourist scale. The forces behind it have strong geo-political motivations, and it’s too early to comment on all the reasons.

Shaila Bano: Exactly. That attack was meant to strike at the very core of the Indian belief that Hindus and Muslims can live peacefully together — especially when something like this happens on such a large tourist scale. The forces behind it have strong geo-political motivations, and it’s too early to comment on all the reasons.

But one thing is certain — the people of Kashmir today are not the same as before. You can see many of them coming out in support of unity and peace. They might have been misguided earlier, but at heart, an average Kashmiri always stands for humanity.

Sekhar: Whew… that’s way too much information for me to process right now.

Sekhar: Whew… that’s way too much information for me to process right now.

Shaila Bano: Heheheh! Oh, I’ve only scratched the surface. If you’re interested, there’s a lot more — how ground-level networks operate, the roles of organizations like Indian Mujahideen, Jaish-e-Mohammed, Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, SIMI, Resistance Front, change of the names of organisations, regional political links, power players, developmental issues, the war of narratives, non-state actors, and how all these elements subtly operate at the ground level.

Shaila Bano: Heheheh! Oh, I’ve only scratched the surface. If you’re interested, there’s a lot more — how ground-level networks operate, the roles of organizations like Indian Mujahideen, Jaish-e-Mohammed, Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, SIMI, Resistance Front, change of the names of organisations, regional political links, power players, developmental issues, the war of narratives, non-state actors, and how all these elements subtly operate at the ground level.

Sekhar: Not anymore, please! Let’s get some coffee and chill for a while — I need to process all this first.

Sekhar: Not anymore, please! Let’s get some coffee and chill for a while — I need to process all this first.

Discover more from The Critilizers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.