Source: Vecteezy

![]() Mona: Hi Teja. I need to talk to you about something important.

Mona: Hi Teja. I need to talk to you about something important.

![]() Teja: :Not now, Mona. And if it’s about your “Mission MLA ” again, I’m out. No mood for a political debate right now.

Teja: :Not now, Mona. And if it’s about your “Mission MLA ” again, I’m out. No mood for a political debate right now.

![]() Mona: Teja… I always thought I was your favorite girlfriend. You have money, influence, and power now. Can’t you fulfill just this one wish of mine?

Mona: Teja… I always thought I was your favorite girlfriend. You have money, influence, and power now. Can’t you fulfill just this one wish of mine?

![]() Teja: Darling, politics isn’t like modeling. It’s far more serious. You need a lot more knowledge and preparation. At best, with connections and money, we might be able to get you a ticket—but managing everything after that is a whole different game.

Teja: Darling, politics isn’t like modeling. It’s far more serious. You need a lot more knowledge and preparation. At best, with connections and money, we might be able to get you a ticket—but managing everything after that is a whole different game.

![]() Mona: I’ll learn. I’ll work hard. I’ll go to the gym every day and enhance my appearance. People will like me! And now that the Women’s Reservation Bill has been passed, we should take advantage of it and win an election.

Mona: I’ll learn. I’ll work hard. I’ll go to the gym every day and enhance my appearance. People will like me! And now that the Women’s Reservation Bill has been passed, we should take advantage of it and win an election.

![]() Teja: This is exactly why I’m hesitant to support you. The way you speak shows you’re not ready. You can’t win elections just by going to the gym. And you’re aiming to contest from Tamil Nadu? Even two truckloads of money won’t help us if you continue talking like this.

Teja: This is exactly why I’m hesitant to support you. The way you speak shows you’re not ready. You can’t win elections just by going to the gym. And you’re aiming to contest from Tamil Nadu? Even two truckloads of money won’t help us if you continue talking like this.

![]() Mona: Then teach me, Teja. I’ll learn from you. But please—don’t just suggest a bunch of books. Go through them yourself and train me. If you won’t help me with this, I’m leaving… and you’ll never see me again.

Mona: Then teach me, Teja. I’ll learn from you. But please—don’t just suggest a bunch of books. Go through them yourself and train me. If you won’t help me with this, I’m leaving… and you’ll never see me again.

![]() Teja: So I become your political coach-slash-boyfriend-slash-human audiobook?

Teja: So I become your political coach-slash-boyfriend-slash-human audiobook?

![]() Teja: Okay. So, Tamil Nadu isn’t like other states—you need to understand Dravidian politics and its background.

Teja: Okay. So, Tamil Nadu isn’t like other states—you need to understand Dravidian politics and its background.

![]() Mona: Dravidian politics sounds really interesting! Wait… does Rahul Dravid or his family have anything to do with it?

Mona: Dravidian politics sounds really interesting! Wait… does Rahul Dravid or his family have anything to do with it?

![]() Teja: For God’s sake, Mona, please don’t try to figure this out on your own. Just listen and try to grasp what I’m telling you. This has absolutely nothing to do with Rahul Dravid. The foundation of Dravidian politics lies in understanding the Dravidian ideology and related historical theories—like the Aryan-Dravidian divide, the Justice Party, the Self-Respect Movement, the Non-Brahmin Movement, and so on.

Teja: For God’s sake, Mona, please don’t try to figure this out on your own. Just listen and try to grasp what I’m telling you. This has absolutely nothing to do with Rahul Dravid. The foundation of Dravidian politics lies in understanding the Dravidian ideology and related historical theories—like the Aryan-Dravidian divide, the Justice Party, the Self-Respect Movement, the Non-Brahmin Movement, and so on.

And no, it also has nothing to do with Kartik Aaryan either!

![]() Mona: (laughs) Okay, okay. Please go on, Teja. Help me understand all this. At the very least, I want to learn something even if I don’t win an election.

Mona: (laughs) Okay, okay. Please go on, Teja. Help me understand all this. At the very least, I want to learn something even if I don’t win an election.

![]() Teja: I’m not going to dive deep into ideologies and theories right now, but I’ll start with the beginnings of Dravidian politics. That’ll give you an idea of the larger context and the multiple dimensions we’ll need to explore.

Teja: I’m not going to dive deep into ideologies and theories right now, but I’ll start with the beginnings of Dravidian politics. That’ll give you an idea of the larger context and the multiple dimensions we’ll need to explore.

![]() Mona: That sounds great! You really know how to teach me—that’s one of the reasons I like you.

Mona: That sounds great! You really know how to teach me—that’s one of the reasons I like you.

![]() Teja: Alright, let’s begin.

Teja: Alright, let’s begin.

The Beginnings:

Dravidian politics started taking shape in the late 19th century and gained real prominence in the early 20th century. It began in the then Madras Province and was primarily led by non-Brahmins.

The movement emerged due to the lack of representation of non-Brahmins in government jobs and public services. A British-conducted survey (from 1892 to 1904) revealed shocking disparities:

- Out of 21 assistant engineers, 16 were Brahmins.

- Out of 140 deputy collectors, 107 were Hindus, and 77 of them were Brahmins.

- Out of 128 permanent district munsifs, 118 were Hindus, and 93 were Brahmins.

- Even in the All India Congress Committee, 14 out of 15 members from Madras Province were Brahmins.

This was despite the Brahmin population being just 2 to 3% of the total population at that time in Madras Province.

These numbers surprised the British government and gradually led to demands for reservations. There were even calls to conduct separate exams for Brahmins and non-Brahmins to level the playing field.

As these demands gained traction, a political movement started taking shape. It wasn’t just political—there were literary developments as well. For example, texts like Shambuka Vadha were written as critiques against Brahminical or Vedic dominance.

![]() Mona: OMG, such a huge disparity! The Brahmins dominated all the political and bureaucratic spheres—that’s really unfair. Of course, other communities had to start a movement. I get it now! I’ll stand with the underrepresented people. I’ll support the weaker sections. I’ll start making Instagram reels condemning this discrimination!

Mona: OMG, such a huge disparity! The Brahmins dominated all the political and bureaucratic spheres—that’s really unfair. Of course, other communities had to start a movement. I get it now! I’ll stand with the underrepresented people. I’ll support the weaker sections. I’ll start making Instagram reels condemning this discrimination!

![]() Teja: Mona, please! This is exactly why I get nervous. I’ve just started explaining things, and you’re already planning reels. Let me dive deeper into this topic. But first, promise me—no reels. Just listen and try to understand, okay?

Teja: Mona, please! This is exactly why I get nervous. I’ve just started explaining things, and you’re already planning reels. Let me dive deeper into this topic. But first, promise me—no reels. Just listen and try to understand, okay?

Deep Dive:

At a surface level, if you only look at the survey data, it might seem like a single community dominated the bureaucracy in the former Madras Province, despite making up a very small portion of the population.

But there are multiple theories and arguments, from different perspectives. Some are academic, but I’ll simplify them so they’re easy to follow.

To understand the situation back then, it’s important to know the socio-economic background of the time.

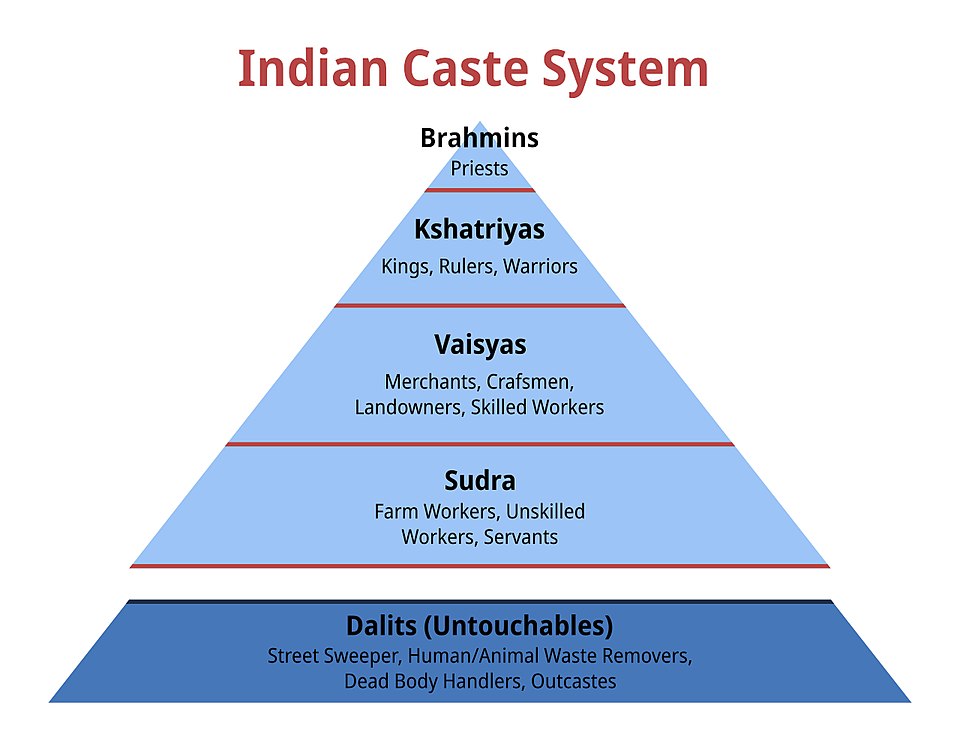

India broadly followed the Varna system, which categorized people into four Varnas:

- Brahmins (priests and scholars)

- Kshatriyas (warriors)

- Vaishyas (traders)

- Shudras (laborers)

Source: Britannica

This classification is mentioned in the Purusha Sukta of the Rigveda. There are other interpretations, theories and Mentions concerning the Jati and Varna systems- a topic best explored at another time

Later, during the post-Vedic period, the Jati system emerged—what we now commonly call the caste system. Jatis were often based on occupation.

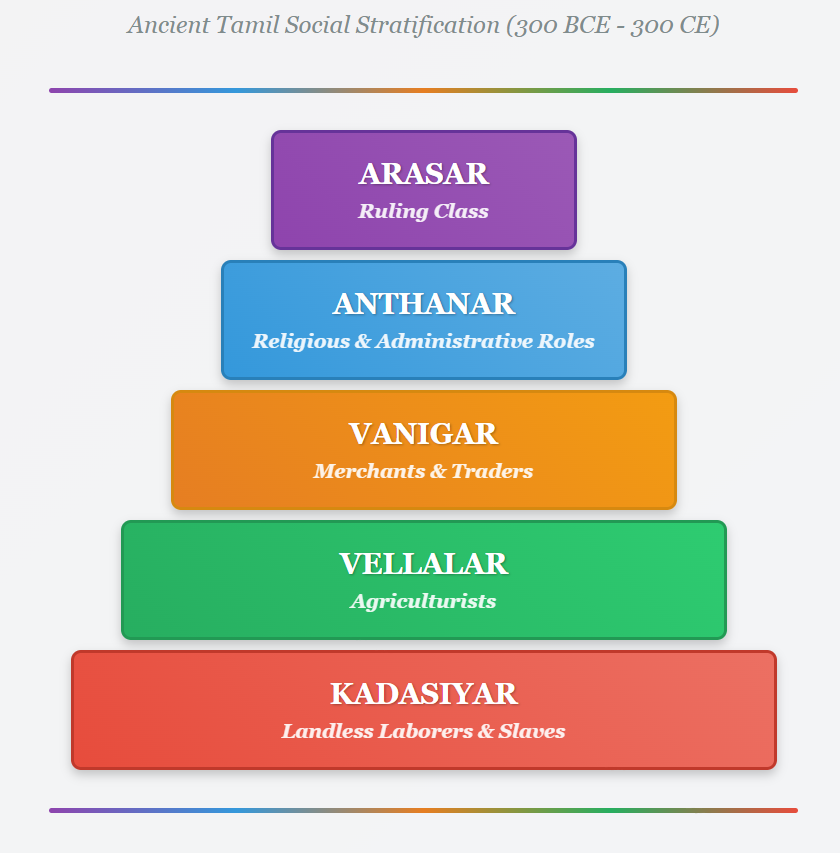

Now, the Varna-Jati model is not neatly applicable to South India. The Tamil social structure developed differently, with its own form of social stratification.

In traditional Tamil society, the divisions were:

- Arasar (ruling class)

- Anthanar (religious and administrative roles)

- Vanigar (merchants and traders)

- Vellalar (agriculturists)

- Kadasiyar (landless laborers and slaves)

- And several tribal communities like Kadambar, Maravar, Puliyar, etc.

There was no clear mapping of this structure to the Varna system seen in the north. Tolakappiyam(authored by Tolakappiyar) and various other Sangam- era texts provide insights into the social structure of ancient south India.

![]() Mona: Ah, okay! So they had their own kind of social division or stratification—that makes sense now.

Mona: Ah, okay! So they had their own kind of social division or stratification—that makes sense now.

![]() Teja: Exactly. That’s why you typically don’t see a distinct Kshatriya class in South India, except in a few regions of Andhra Pradesh. It is usually Brahmins and Non Brahmins

Teja: Exactly. That’s why you typically don’t see a distinct Kshatriya class in South India, except in a few regions of Andhra Pradesh. It is usually Brahmins and Non Brahmins

![]() Mona: And now I understand why the Brahmin population is smaller in the South. But still—what explains their dominance back then?

Mona: And now I understand why the Brahmin population is smaller in the South. But still—what explains their dominance back then?

![]() Teja: Good question. Actually, across most of India, Brahmins were never numerically dominant. But due to early access to education and scriptures, they had a traditional advantage.

Teja: Good question. Actually, across most of India, Brahmins were never numerically dominant. But due to early access to education and scriptures, they had a traditional advantage.

Historians believe that Vedic culture was introduced to the South by sage Agastya.

To simplify it, sociologists use the concepts of entrenched castes and ascribed castes:

- Entrenched castes are those who historically benefited from educational and religious privileges—typically Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas.

- Ascribed status refers to a social position assigned at birth or assumed involuntarily. Many Shudra castes improved their status over time through land ownership, wealth, or political power. These are sometimes called ascribing castes.

For Example:- Reddys and Kammas in Andhra

- Mudaliyars in Tamil Nadu

- Yadavs in Uttar Pradesh

These communities, though historically part of the Shudra varna, have become economically and politically powerful. Sociologists refer to them as “Dominant Castes” or “New Kshatriyas”.

In many states today, these dominant castes compete among themselves for political power, often overshadowing even the upper castes.

![]() Mona: Now I understand the difference between the traditional Varna system and the concept of dominant castes. But tell me, were these castes in a disadvantaged position during that period? Is that why they started making political demands?

Mona: Now I understand the difference between the traditional Varna system and the concept of dominant castes. But tell me, were these castes in a disadvantaged position during that period? Is that why they started making political demands?

![]() Teja: There are several reasons behind it. Some castes were indeed at a disadvantage, while others were not. We’ll discuss this in more detail in the coming days. But for now, I’ll give you a basic understanding.

Teja: There are several reasons behind it. Some castes were indeed at a disadvantage, while others were not. We’ll discuss this in more detail in the coming days. But for now, I’ll give you a basic understanding.

During the medieval period, the socio-economic structure of India was quite different. There was a thriving artisan class—sculptors, potters, goldsmiths, carpenters, and so on. In Andhra Pradesh, these communities were often grouped under the term Panchanam (a collective term for artisan castes).

To appreciate their importance, you can trace the evolution of pottery from the Indus Valley Civilization onwards. These artisan communities were so well-organized that many had their own guilds. In fact, the grandeur of Dravidian temple architecture—like the Pallava, Chola, Hoysala, and Vijayanagara styles—testifies to the skills of these artisans.

The Ramappa Temple in Telangana, for instance, is famously named after its chief sculptor.

![]() Mona: If they were doing so well, then why did they get involved in political movements? I’m a bit confused—could you clarify?

Mona: If they were doing so well, then why did they get involved in political movements? I’m a bit confused—could you clarify?

![]() Teja: I was just getting to that point. I brought up their historical success to show the depth of their contributions to society. But things changed drastically later.

Teja: I was just getting to that point. I brought up their historical success to show the depth of their contributions to society. But things changed drastically later.

The Subaltern School of historiography focuses on the history of the masses—ordinary people, rather than kings and elites. Even among subaltern scholars, there’s debate about the exact position of artisan communities and the nature of social stratification in earlier times.

What’s important to understand is that with the advent of the Industrial Revolution and discriminatory British policies, these artisan classes began to struggle economically.

For instance, India was once renowned for its Muslin and Calico textiles, which were in high demand across Europe during the early British rule. However, with the rise of mechanized British textiles, traditional Indian arts and crafts lost their markets.

India was turned into a market for British-manufactured goods, and local craftspeople suffered heavily.

For more on this, even the NCERT Fine Arts textbook (Part 2, Chapter 8: The Living Art Traditions of India) offers valuable insights into the once-thriving traditional arts.

![]() Mona: Ohh… so these communities lost their livelihoods. Their survival must have become very difficult.

Mona: Ohh… so these communities lost their livelihoods. Their survival must have become very difficult.

![]() Teja: Exactly. Many couldn’t continue with their traditional occupations. They were forced to take up low-paying jobs in British-run mills or work as agricultural laborers.

Teja: Exactly. Many couldn’t continue with their traditional occupations. They were forced to take up low-paying jobs in British-run mills or work as agricultural laborers.

![]() Mona: That must have been really hard for them… such a massive drop in their social and economic status. That’s really sad.

Mona: That must have been really hard for them… such a massive drop in their social and economic status. That’s really sad.

![]() Teja: Yes, it was. Many faced severe hardships just to survive. And the limited number of mills and industries at the time couldn’t accommodate the growing population of displaced artisans. Those who turned to agricultural labor were even worse off.

Teja: Yes, it was. Many faced severe hardships just to survive. And the limited number of mills and industries at the time couldn’t accommodate the growing population of displaced artisans. Those who turned to agricultural labor were even worse off.

The growing dissatisfaction among them eventually manifested in the form of riots and revolts—like the Indigo Rebellion, the Pabna Agrarian Revolt, and the Telangana Movement, to name a few.

Meanwhile, although British revenue policies destroyed much of the existing social fabric, some groups benefited—specifically the dominant castes, who were from intermediate caste groups (usually categorized under the Shudra varna but socially considered higher due to wealth or land ownership).

These dominant castes had numerical strength, and British land revenue policies enabled them to accumulate more land. (How this happened, and the arguments surrounding it, is a complex topic for another day—but this overview should give you a decent understanding for now.)

![]() Mona: Okay, so new landlords emerged. As they became dominant, they started demanding political power. Meanwhile, the artisan classes, having lost their traditional importance, began raising political demands just to survive.

Mona: Okay, so new landlords emerged. As they became dominant, they started demanding political power. Meanwhile, the artisan classes, having lost their traditional importance, began raising political demands just to survive.

![]() Teja: Exactly. The entrenched castes—like the Brahmins, and to a lesser extent the Kshatriyas (though typically absent in the South)—were traditionally dependent on education and were already politically active. So, when English education became available, it was easier for them to adapt and benefit from it.(One of the reasons for Brahmin dominance in the Indian National Congress during its formative years was that it was primarily the educated Brahmins who initiated the political struggle and took the lead in forming political organizations.

Teja: Exactly. The entrenched castes—like the Brahmins, and to a lesser extent the Kshatriyas (though typically absent in the South)—were traditionally dependent on education and were already politically active. So, when English education became available, it was easier for them to adapt and benefit from it.(One of the reasons for Brahmin dominance in the Indian National Congress during its formative years was that it was primarily the educated Brahmins who initiated the political struggle and took the lead in forming political organizations.

The British, when appointing bureaucrats and clerical staff, naturally preferred the educated classes—whether as translators (Dubashis), or while codifying Hindu and Muslim laws, etc. These communities became their go-to choice.

One important point here is: the educated class wasn’t necessarily wealthy, while the artisan class was thriving economically, producing goods and running businesses. But British policies disrupted this balance by undermining Indian industries, pushing artisan communities into economic hardship. As their industries collapsed, competition for jobs increased.

![]() Mona: So, you’re saying that the underrepresentation of other communities was mainly caused by British policies?

Mona: So, you’re saying that the underrepresentation of other communities was mainly caused by British policies?

![]() Teja: What I’m saying is—if you’re wondering why one particular community dominated the bureaucracy, it’s essential to look at the broader socio-economic context. British policies were a major reason for the collapse of the artisan class, which in turn affected their ability to compete in the new English-education-based administrative structure.

Teja: What I’m saying is—if you’re wondering why one particular community dominated the bureaucracy, it’s essential to look at the broader socio-economic context. British policies were a major reason for the collapse of the artisan class, which in turn affected their ability to compete in the new English-education-based administrative structure.

This explanation is meant to give a historical perspective, not to justify or cover up the injustice done to certain communities, especially Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

If you want to understand in more depth how Indian handicrafts and the economy were destroyed, you can explore:

- Charter Act of 1813

- Charter Act of 1833

- Poverty and Un-British Rule in India – by Dadabhai Naoroji (Link to book)

- Economic Drain Theory – by Dadabhai Naoroji

- Economic History of India – by R.C. Dutt

![]() Mona: So eventually, it turned into Brahmins vs. Non-Brahmins?

Mona: So eventually, it turned into Brahmins vs. Non-Brahmins?

![]() Teja: It’s not entirely accurate to frame it simply as Brahmins vs. Non-Brahmins, but yes, the issue often overlaps with the Non-Brahmin movement.

Teja: It’s not entirely accurate to frame it simply as Brahmins vs. Non-Brahmins, but yes, the issue often overlaps with the Non-Brahmin movement.

The leaders of this movement claimed they were opposing Brahminical dominance, especially in administrative and educational spheres. However, the movement sometimes stirred anti-Brahmin sentiment, particularly in southern India.

For example, E.V. Ramasamy (Periyar) in his 1957 speeches openly called for driving Brahmins out of Tamil land—a clear instance of such rhetoric.

![]() Mona: Okay… now I’m slowly starting to understand.

Mona: Okay… now I’m slowly starting to understand.

![]() Teja: Good. But this isn’t something you grasp all at once. I’ll explain everything in detail—but over time. Let’s sit down this weekend, and I’ll go through it properly with you.

Teja: Good. But this isn’t something you grasp all at once. I’ll explain everything in detail—but over time. Let’s sit down this weekend, and I’ll go through it properly with you.

![]() Mona: Please begin with why the term “Dravidian” was used, and explain the background of Tamil Nadu politics.

Mona: Please begin with why the term “Dravidian” was used, and explain the background of Tamil Nadu politics.

![]() Teja: I will, I promise. But first—you must promise not to speak in public or make any reels about this in the meantime!

Teja: I will, I promise. But first—you must promise not to speak in public or make any reels about this in the meantime!

Discover more from The Critilizers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Good one. Though I am not much in to politics and all, you should be doing some great work. Keep doing the good work 👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼🚀🚀🚀🚀

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very fine piece of writing. Thoroughly researched to make it precise and engagingly informative. Good job!!

LikeLiked by 1 person