![]() Mona: Hi Teja. You said we’d discuss things over the weekend. Shall we continue?

Mona: Hi Teja. You said we’d discuss things over the weekend. Shall we continue?

![]() Teja: Oh, you actually took that seriously? I thought you’d forget! Didn’t expect this level of commitment.

Teja: Oh, you actually took that seriously? I thought you’d forget! Didn’t expect this level of commitment.

![]() Mona: I told you earlier too—I’m serious about this. Now come on, start with the topic. Why the name “Dravidian” and all? Should we go to the bar and talk it out there?

Mona: I told you earlier too—I’m serious about this. Now come on, start with the topic. Why the name “Dravidian” and all? Should we go to the bar and talk it out there?

![]() Teja: Nope, not the bar. If we go there, you’ll think I’m just another drunk guy ranting. And if you get drunk, you won’t be listening—you’ll either be dancing, puking, or crying. Let’s stick to chai and sutta for this discussion.

Teja: Nope, not the bar. If we go there, you’ll think I’m just another drunk guy ranting. And if you get drunk, you won’t be listening—you’ll either be dancing, puking, or crying. Let’s stick to chai and sutta for this discussion.

![]() Mona: Okay, I’ll get those sorted. Now start. Last time, you gave a nice intro about the beginnings of the Dravidian movement. That was good. But now tell me—why the word “Dravidian”?

Mona: Okay, I’ll get those sorted. Now start. Last time, you gave a nice intro about the beginnings of the Dravidian movement. That was good. But now tell me—why the word “Dravidian”?

![]() Teja: To put it simply, the term “Dravidian” refers to ethnic, racial, and linguistic identities—especially of the people in South India. There are multiple theories and debates. Some scholars and thinkers see Dravidians as a completely separate race from North Indians(Usually Upper Castes) or Brahmins(South India). Others see them more as a distinct linguistic group rather than a separate race.

Teja: To put it simply, the term “Dravidian” refers to ethnic, racial, and linguistic identities—especially of the people in South India. There are multiple theories and debates. Some scholars and thinkers see Dravidians as a completely separate race from North Indians(Usually Upper Castes) or Brahmins(South India). Others see them more as a distinct linguistic group rather than a separate race.

![]() Mona: Oh, this sounds complicated. Are you saying South Indians are different from the North Indian population? Ah, now I get it—like how South Indians, especially Tamils, dress and speak differently.

Mona: Oh, this sounds complicated. Are you saying South Indians are different from the North Indian population? Ah, now I get it—like how South Indians, especially Tamils, dress and speak differently.

![]() Teja: I agree, there are cultural differences. But those could be due to many reasons—like climate, geography, topography, and so on. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re different in terms of race or ethnicity.

Teja: I agree, there are cultural differences. But those could be due to many reasons—like climate, geography, topography, and so on. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re different in terms of race or ethnicity.

![]() Mona: See! You’re making it even more confusing now. You said the word refers to ethnicity, race, or a linguistic group, and now you’re saying cultural differences could be due to other reasons. Just make it simple, please. Don’t try to show off your knowledge—just help me understand this stuff.

Mona: See! You’re making it even more confusing now. You said the word refers to ethnicity, race, or a linguistic group, and now you’re saying cultural differences could be due to other reasons. Just make it simple, please. Don’t try to show off your knowledge—just help me understand this stuff.

![]() Teja: I get it. But I said that because there are multiple theories, debates, and discussions around this topic. It’s not something with one clear answer. Still, I’ll try—let me start by explaining the whole Aryan-Dravidian debate.

Teja: I get it. But I said that because there are multiple theories, debates, and discussions around this topic. It’s not something with one clear answer. Still, I’ll try—let me start by explaining the whole Aryan-Dravidian debate.

![]() Mona: Ugh, again with the fancy terms! If I try to guess anything myself, you’ll just make fun of me. So please, keep it simple.

Mona: Ugh, again with the fancy terms! If I try to guess anything myself, you’ll just make fun of me. So please, keep it simple.

![]() Teja: Alright, let’s dive in.

Teja: Alright, let’s dive in.

Aryan–Dravidian Debate—Before diving into the actual debate, let me quickly lay out the timeline of Indian history for you.

After the Stone Age, the major phase was the Harappan Civilization (roughly 3000 BCE to 1800 BCE), also known as the Indus Valley Civilization—part of the Bronze Age. While it’s commonly dated to around 3000 BCE, excavations at sites like Bhirrana (Haryana) and Amri have produced evidence going as far back as 5000 BCE, making it one of the oldest known civilizations in the world.

Interestingly, the first traces of the Indus Valley Civilization were stumbled upon by British engineers in the late 1850s, who were searching for ballast for a railway line in what is now Pakistan. But the discovery story actually begins earlier—around March or April 1829, when Charles Masson visited a massive mound near the village of Harappa, beside an abandoned course of the Ravi River.

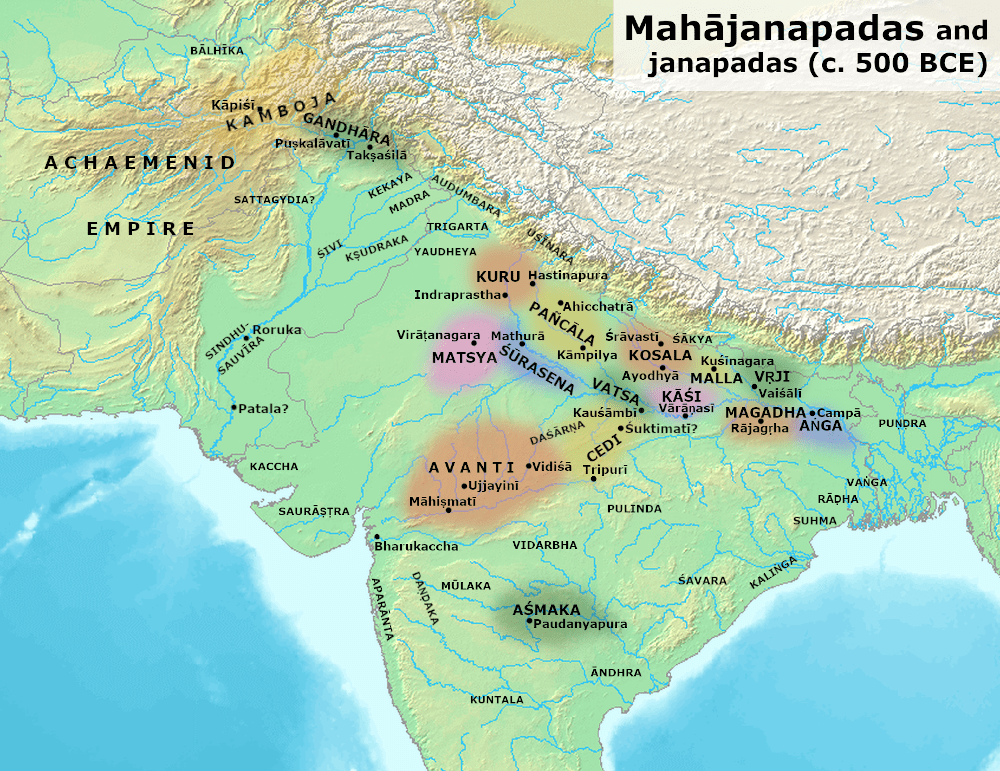

This period was followed by the Vedic Period (roughly 1800 BCE to 600 BCE), often associated with Aryan culture (also called Aryavarta) and identified as part of the Iron Age. After that came the Mahajanapada period and others—but let’s not jump too far ahead. For now, we’ll stick to this foundational timeline.

(Quick note: Different historians have proposed slightly varying timelines, but these differences are usually in the range of 2–3 centuries—not drastically off.)

Timeframes suggested by notable historians:

- John Marshall: 3250–2750 BCE

- Mortimer Wheeler: 2500–1700 BCE

- D.P. Agarwal: 2300–1750 BCE (Metropolitan centers: 2350–2000 BCE; Peripheral sites: 2200–1700 BCE)

- G.F. Dales: 2154–1864 BCE (for the mature Harappan phase)

![]() Mona: Oh, so basically you’re walking me through our historical timeline. First came the Indus Valley period, then the Vedic period, right? How did I miss all this? I mean, me and my friends talk a lot—but clearly, history never made it into our conversations.

Mona: Oh, so basically you’re walking me through our historical timeline. First came the Indus Valley period, then the Vedic period, right? How did I miss all this? I mean, me and my friends talk a lot—but clearly, history never made it into our conversations.

![]() Teja: My dear, you and your friends mostly gossip about who’s dating whom. At best, that content could be used to write some triangular, quadrilateral—or if you stretch it—polygonal love stories! Anyway, let me get back to the topic I was on.

Teja: My dear, you and your friends mostly gossip about who’s dating whom. At best, that content could be used to write some triangular, quadrilateral—or if you stretch it—polygonal love stories! Anyway, let me get back to the topic I was on.

![]() Mona: You always mock me and my friends! But fine, go ahead. Continue your history gyaan.

Mona: You always mock me and my friends! But fine, go ahead. Continue your history gyaan.

![]() Teja: So, the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was an urban society—these folks seriously knew their town planning. What’s mind-blowing is how uniform their cities were, no matter how far apart. Their script is still a mystery—undeciphered to this day. But archaeological findings give us insights into their water systems, social structures, urban design, and more. Though, of course, historians love to interpret things in their own ways.

Teja: So, the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was an urban society—these folks seriously knew their town planning. What’s mind-blowing is how uniform their cities were, no matter how far apart. Their script is still a mystery—undeciphered to this day. But archaeological findings give us insights into their water systems, social structures, urban design, and more. Though, of course, historians love to interpret things in their own ways.

Interestingly, even before the peak of the IVC, there was an agricultural phase that laid the foundation for its urban nature. Early Harappan sites like Amri, and some Chalcolithic sites, were known for their rural, village-style settlements.

On the other hand, the early Vedic period was more pastoral in nature. People weren’t exactly settled down yet. They were mostly moving around, looking for suitable grazing land. That’s why cows were a big deal—they literally represented wealth.

Later on, with the invention of the iron plough, people started clearing forests and settling down. Villages evolved into towns, and from there, emerged the Janapadas and eventually the Mahajanapadas—sixteen large kingdoms like Anga, Vanga, Avanti, Asmaka, and more.

This period of the Mahajanapadas is often referred to as the Second Urbanisation..

![]() Mona: Okay, now I get it. The word Aryan or Aryan culture basically refers to the Vedic culture—or mostly what we now call Hindu culture. But what exactly is the debate?

Mona: Okay, now I get it. The word Aryan or Aryan culture basically refers to the Vedic culture—or mostly what we now call Hindu culture. But what exactly is the debate?

![]() Teja: I’m getting to that. But first, let me clear up a few things.

Teja: I’m getting to that. But first, let me clear up a few things.

As I already mentioned, the Indus Valley Civilization came before the Aryan culture. It’s believed that the IVC spanned over 13 lakh square kilometers! It was one of the earliest and greatest civilizations of its time—on par with Mesopotamian, Babylonian, and other ancient civilizations.

Now, here’s the important part: the discovery of this civilization in India gave Indians a huge boost in confidence. It showed that our culture, our civilization, and our history were in no way inferior to those of the colonial European powers—who used to claim it was the “white man’s burden” to civilize the so-called “barbaric” or “savage” people. They called their rule “benevolent despotism”—which is just a fancy way of saying “we’re ruling you for your own good.”

![]() Mona: Wow, that’s actually really nice to know—we had such a rich civilization! I recently watched a couple of movies and series about the Greeks. I didn’t quite get the historical references or symbolism, but I loved the storytelling and the way the characters were portrayed. Honestly, I’d love to act in a historical drama like that. Teja, why don’t you produce one for me?

Mona: Wow, that’s actually really nice to know—we had such a rich civilization! I recently watched a couple of movies and series about the Greeks. I didn’t quite get the historical references or symbolism, but I loved the storytelling and the way the characters were portrayed. Honestly, I’d love to act in a historical drama like that. Teja, why don’t you produce one for me?

![]() Teja: Oh, now you want me to fund your political debut and produce a movie for you? What’s your plan here? You want to see me bankrupt, begging on the streets, and sleeping on a railway platform? Please, let’s not derail this conversation and stop coming up with new business ideas.

Teja: Oh, now you want me to fund your political debut and produce a movie for you? What’s your plan here? You want to see me bankrupt, begging on the streets, and sleeping on a railway platform? Please, let’s not derail this conversation and stop coming up with new business ideas.

![]() Mona: Relax! I was just joking. No need to get so worked up. Go on, continue!

Mona: Relax! I was just joking. No need to get so worked up. Go on, continue!

![]() Teja: So, the main point of discussion here is the Aryan Invasion/Migration Theory. First, I’ll explain what this theory is about, and then we’ll talk about the people who supported it—and the evidence they used to back it up.

Teja: So, the main point of discussion here is the Aryan Invasion/Migration Theory. First, I’ll explain what this theory is about, and then we’ll talk about the people who supported it—and the evidence they used to back it up.

![]() Mona: Invasion as in war? Now we’re talking! Sounds interesting—go on.

Mona: Invasion as in war? Now we’re talking! Sounds interesting—go on.

![]() Teja: Yep, that’s right.

Teja: Yep, that’s right.

Aryan Invasion / Migration:

The theory says that the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was already flourishing, and then the Aryans—people from other parts of the world—migrated and possibly invaded the IVC population.

Now, there are multiple arguments about who exactly the Aryans were. Let me list a few popular theories:

- They came from the steppe grasslands of Eurasia – (Max Muller)

- They came from the Arctic region – (Lokamanya Tilak)(RigVeda Day and night for 6 months)

- They belonged to the Tibetan region – (Dayananda Saraswati)

- They originated from the Persian region, pointing to similarities between Zoroastrianism / Avesta texts and the Vedas.(Boghuz Kai Inscription)

- Indigenous (Dr Sampooranand and AC Das)

And there are plenty more details based on which they spoke about their origins, but I don’t want to turn this into a full-on historical documentary—so let’s keep it short.

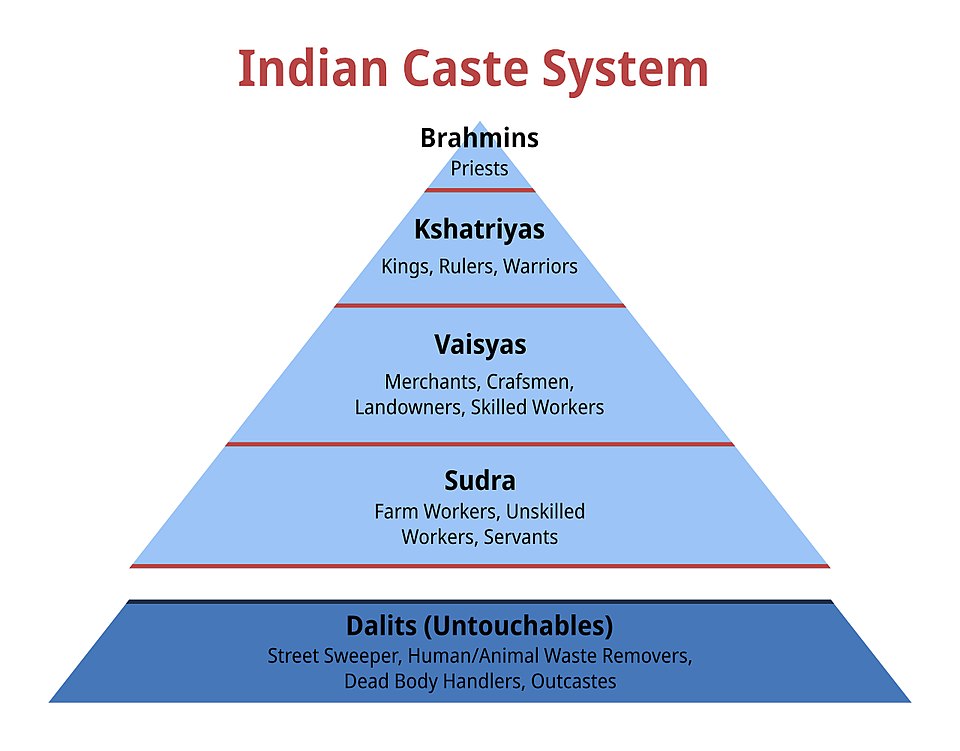

Now, here’s the core point: as I mentioned earlier, Rigveda and several other texts talk about the Varna system—basically a social pyramid. (I’m skipping over the detailed theories of Varna and Jati for now, we can fall into later.)

In short: the top three castes—Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas—were known as the Dvija castes, or the “twice-born.” The idea was that they had earned their status through good deeds in their past lives.

Shudras, sitting at the bottom of the pyramid, were mostly assigned the role of providing services to the other three groups.

![]() Mona: So basically, the Vedic society had four social divisions, and each one had specific roles and responsibilities. And the Shudras were meant to serve the other three?

Mona: So basically, the Vedic society had four social divisions, and each one had specific roles and responsibilities. And the Shudras were meant to serve the other three?

![]() Teja: Yes, and there’s another term you’ll often come across in Vedic literature—Dasyus or Dasas. There are references to Lord Indra (also called Purandhara) destroying their forts. Historians have interpreted these verses to suggest that the Aryans invaded the local population—believed to be the people of the Indus Valley—and assigned them a lower social status.

Teja: Yes, and there’s another term you’ll often come across in Vedic literature—Dasyus or Dasas. There are references to Lord Indra (also called Purandhara) destroying their forts. Historians have interpreted these verses to suggest that the Aryans invaded the local population—believed to be the people of the Indus Valley—and assigned them a lower social status.

These groups were classified as Shudras (who still had a higher status compared to Dalits) and Ati-Shudras (Dalits or Panchamas or Avarnas (outside the Varna system)).

![]() Mona: So, basically, what they’re saying is that the Aryans—or the Vedic people—invaded the locals and turned them into slaves?

Mona: So, basically, what they’re saying is that the Aryans—or the Vedic people—invaded the locals and turned them into slaves?

![]() Teja: Yes! And it’s believed that many of the locals who lost that conflict moved down south, beyond the Vindhyas, and settled there.

Teja: Yes! And it’s believed that many of the locals who lost that conflict moved down south, beyond the Vindhyas, and settled there.

Dravidian thinkers argue that these people were the original inhabitants—aboriginals—with a culture quite different from that of the Vedic Aryans. They claim that when Vedic culture later reached the south, it pushed the native culture down and lowered their social status.

This theory started gaining political traction in the late 19th century, especially in Madras Province. Dravidian intellectuals began to argue that the Indus Valley Civilization and their own southern traditions had more in common than either did with the Vedic society.

That’s also when Brahmins began to be seen as the representatives of Aryan culture in South India—and that’s how the whole Aryan vs. Dravidian debate really took shape.

![]() Mona: So is this debate only based on the Varna model? Or are there other arguments too that support the Aryan-Dravidian divide?

Mona: So is this debate only based on the Varna model? Or are there other arguments too that support the Aryan-Dravidian divide?

![]() Teja: There are several other arguments that support this theory as well:

Teja: There are several other arguments that support this theory as well:

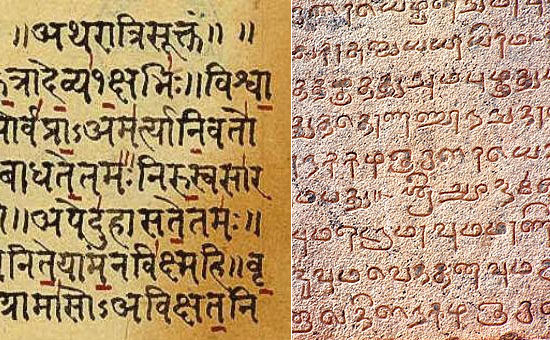

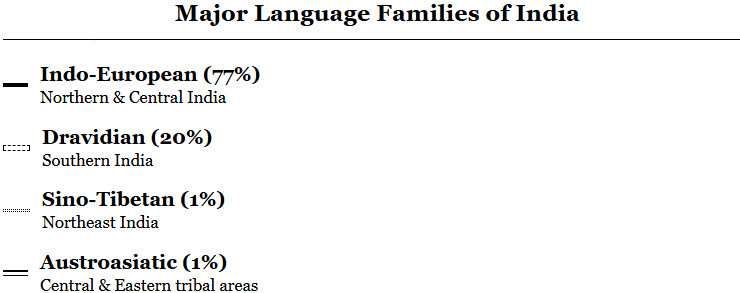

- Orientalists like William Jones discovered similarities between ancient Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin. Sanskrit, along with Hindi, falls under the Indo-European language family. Sanskrit was mostly spoken by Brahmins and Kshatriyas, while Prakrit and Pali were the languages of the common folk.

Even today, there’s an ongoing debate around the Sanskritisation of South Indian languages like Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, etc.—with many locals trying to remove Sanskrit influence from their native tongues. - South Indian languages such as Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Gondi, and even Brahui(Spoken in Balochistan) are classified as Dravidian languages. Some believe Gondi forms the base or primitive structure for the rest.

(We can dive deeper into this when we tackle the language issue in detail later.)

Especially around 1967, there was a major rise in linguistic sentiment in Tamil Nadu—particularly over the imposition of Hindi. That whole saga falls under language politics, which we’ll definitely get to. - Buddhist and Jain texts are primarily written in Pali, Prakrit, and Ardhamagadhi—languages that are much closer to local dialects than Sanskrit.This is one reason why Dravidian supporters often claim ownership of Buddhism, especially since many Buddhist texts critique Vedic rituals. (Even Ambedkar laid the foundation for Neo-Buddhism based on these ideals.)However, Sanskrit supporters counter this by pointing out that Mahayana Buddhism—a major branch of Buddhism—is largely dominated by Sanskrit literature.

![]() Mona: Ohh! So that’s why you said Dravidians might be a linguistic group?

Mona: Ohh! So that’s why you said Dravidians might be a linguistic group?

![]() Teja: Exactly! And there are more cultural arguments that go beyond just language:

Teja: Exactly! And there are more cultural arguments that go beyond just language:

- Worship of Murugan(Subramanya) as the primary deity in Tamil Nadu is one example. It’s believed that Shiva worship is indigenous to South India.

Even the Indus Valley Civilization shows traces of early Shiva worship—like the famous Pashupati seal and signs of linga worship. Some believe Shiva worship actually spread from the South to the North. - Universalisation and Parochialisation: Dravidian thinkers argue that many local deities once worshipped in small regions were gradually absorbed into the larger Hindu pantheon.

This happened especially during the Gupta period, when Hinduism evolved into what we call Puranic Hinduism.

Before that, Vedic texts emphasised gods like Indra, Agni, Vayu, and Varuna, and rituals like Yajnas and Yagas (Ashvamedha, Vajapeya, etc.). Ashvameda yaga( It is beleved that IVC people are not aware of horses and vedic people are dependent on horse drawn chariots in war fare. There is also a ambiguity about the relics of animal found at the Indus Valley site Suktagendor whether it is of horse or not

But later, Vishnu, Shiva, Brahma, and Shakti became the major deities—and many local gods got merged into one form or another. - The style of worship also varies. In many local traditions, you’ll find non-Brahmin priests, and it’s common to offer things like meat and alcohol to the local gods.

Dravidian thinkers see this as a contrast to Brahminical practices.

On the other hand, critics of this theory argue that Hinduism has always allowed diverse forms of worship. For example, the Vamachara path in Hinduism includes such practices.

Even scholars like Ghurye have said that tribals fall within the broader Hindu fold. Some also believe that the Atharva Veda includes elements of tribal knowledge and traditions.

![]() Mona: Dude, this whole explanation is going over my head. Please come back to Earth. All I got so far is—people argued and debated even about which gods to worship!

Mona: Dude, this whole explanation is going over my head. Please come back to Earth. All I got so far is—people argued and debated even about which gods to worship!

![]() Teja: Haha, that much understanding is a good start!

Teja: Haha, that much understanding is a good start!

To add on—there’s also the study of the R1A1 gene(Haplogroup R1a1), which is predominantly found in the Steppe region and is also present in a significant percentage of Brahmin populations in South India.

Then there are recent archaeological findings from Keeladi, which some say support parts of the Dravidian theory—but again, there are plenty of counter-arguments to that too.

Also, the 1931 census conducted by Risley used anthropometry—basically measuring physical traits like skull size, nose shape, etc.—as a way to define race.

This was all before the development of genetic studies.

Today, most scholars agree that Risley’s work is considered pseudo-scientific.

![]() Mona: Now that is making some sense. So, there are basically two layers to this.

Mona: Now that is making some sense. So, there are basically two layers to this.

First, it’s a kind of North–South divide, where the Varna–Jati system fits neatly in the North and aligns with the Vedic (Aryan) texts.

But in the South, the social structure and Varna doesn’t map that clearly. Dominant Castes like Reddys, Kammas, Mudaliyars, etc., were given the status of Shudras(Though enjoyed privileged status)

Second it is Brahmin and Non Brahmin Division Where Brahmins—mostly seen as Aryan reps (since Kshatriyas are rare in the South)—were considered the upper caste, while the non-Brahmin population was grouped under Dravidian identity.

The Dravidian side makes sense to some extent—especially since Dravidian literature grew in influence and probably gave a boost to Dravidian political movements.

![]() Teja: Whoa why are you jumping to conclusions so fast? Slow down, detective Mona!

Teja: Whoa why are you jumping to conclusions so fast? Slow down, detective Mona!

There’s another side to the story too, right?

Some historians like M.R. Sahni , G.L. Possehl, K.A. Nilakanta Sastri and others don’t support the Aryan Invasion theory.

They argue there was no invasion—apart from Mohenjo-Daro, we don’t have strong evidence of mass burials or war casualties.

Even in Mohenjo-Daro, the burial findings aren’t conclusive of any large-scale conflict.

They suggest that the Indus Valley Civilization may have collapsed due to natural causes or environmental changes, not because of an invasion.

Here are some of their points:

- Drying up of rivers like Ghaggar and Hakra, or Saraswati changing course. This theory was proposed by Stein (1931) and Marshall (1931).

It’s supported by palynological data from Rajasthan (yeah, pollen science!). - Mohenjo-Daro was flooded not once, but seven times.

- Tectonic activity—aka earthquakes—was proposed by M.R. Sahni (1952) and later expanded on by R.L. Raikes.

- Other arguments include economic reasons: decline of trade, town planning breaking down, possible epidemics, etc.

G.L. Possehl, in his book Ancient Cities of the Indus, proposed that economic decline and abandonment of Indo-Iranian border villages might have led to the fall of IVC.

Even when it comes to the Varna system, there are multiple interpretations.

Some Vedic texts actually say that Varna was based on occupation or traits, not birth.

There are ideas that Gunas—Sattva, Rajas, Tamas—determine one’s Varna(Bhagavadgeeta).

There’s even a classic example from early Vedic texts where one family has members of all four Varnas!

While Dravidian thinkers viewed the Varna system as a form of social stratification, other scholars interpreted it as a system of occupational division that emphasized the dignity of labour. At the local level, there were also several powerful Shudra kingdoms—examples include the Reddys, Kakatiyas, and Jat dynasties.

![]() Mona: Who are all these folks you keep naming? I’ve never even heard of them—forget magazine covers, I don’t think they’ve even made it to my Instagram feed!

Mona: Who are all these folks you keep naming? I’ve never even heard of them—forget magazine covers, I don’t think they’ve even made it to my Instagram feed!

![]() Teja: They’re historians and archaeologists who’ve worked extensively in this field. The magazines you read usually have models and celebrities on the cover—how can you expect these folks to make it there?

Teja: They’re historians and archaeologists who’ve worked extensively in this field. The magazines you read usually have models and celebrities on the cover—how can you expect these folks to make it there?

![]() Mona: Darling, this whole thing is super exhaustive. I need some time to digest this history buffet!

Mona: Darling, this whole thing is super exhaustive. I need some time to digest this history buffet!

![]() Teja: I totally get it. Too many arguments all at once

Teja: I totally get it. Too many arguments all at once

![]() Mona: Still, thanks for helping me get at least an overview. I’m not totally lost anymore!

Mona: Still, thanks for helping me get at least an overview. I’m not totally lost anymore!

![]() Teja: Don’t worry at all. The whole point was to lay down a strong foundation so you can understand politics better. For instance, you might’ve come across statements by leaders like Udhayanidhi Stalin on Sanatana Dharma. This background will help you grasp the roots of such ideologies.

Teja: Don’t worry at all. The whole point was to lay down a strong foundation so you can understand politics better. For instance, you might’ve come across statements by leaders like Udhayanidhi Stalin on Sanatana Dharma. This background will help you grasp the roots of such ideologies.

Now that we’ve set the stage, I’ll make things even clearer by introducing you to key political personalities of the Dravidian Movement—like Iyothee Thass, Periyar, and others.

And more importantly, you’ll be able to understand the political landscape with a clear, balanced perspective.

I’m just trying to show both sides of the coin—so you don’t get caught in a one-sided narrative.

Discover more from The Critilizers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Like mona said thats a lot of information at one go….but neatly presented…looking forward for more such articles!!

LikeLiked by 1 person